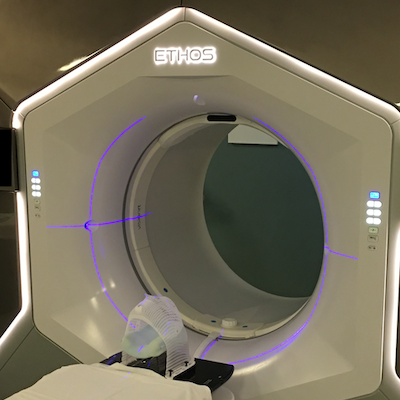

So far I’ve managed to tell my story while ignoring the elephant in the room: death. In March of this year I was diagnosed with an incurable brain cancer known as “glioblastoma.” It’s terminal, meaning I’ll die from it unless something else kills me first. It’s also highly aggressive, meaning it will probably kill me sooner rather than later. I’ve been treated with the standard of care.