The complexity of the networks in which our organization operates is scaffolded by a corpus of mostly-unwritten, tacit knowledge and ‘ways of working’ that we learn mostly from our peers.

The complexity of the networks in which our organization operates is scaffolded by a corpus of mostly-unwritten, tacit knowledge and ‘ways of working’ that we learn mostly from our peers.

Leave the global functions to headquarters, and shift responsibility for the field to those who are actually there (or close by). It sounds perfectly sensible. And, in fact, it is an approach to decentralization adopted by some organizations. What are its implications for learning strategy?

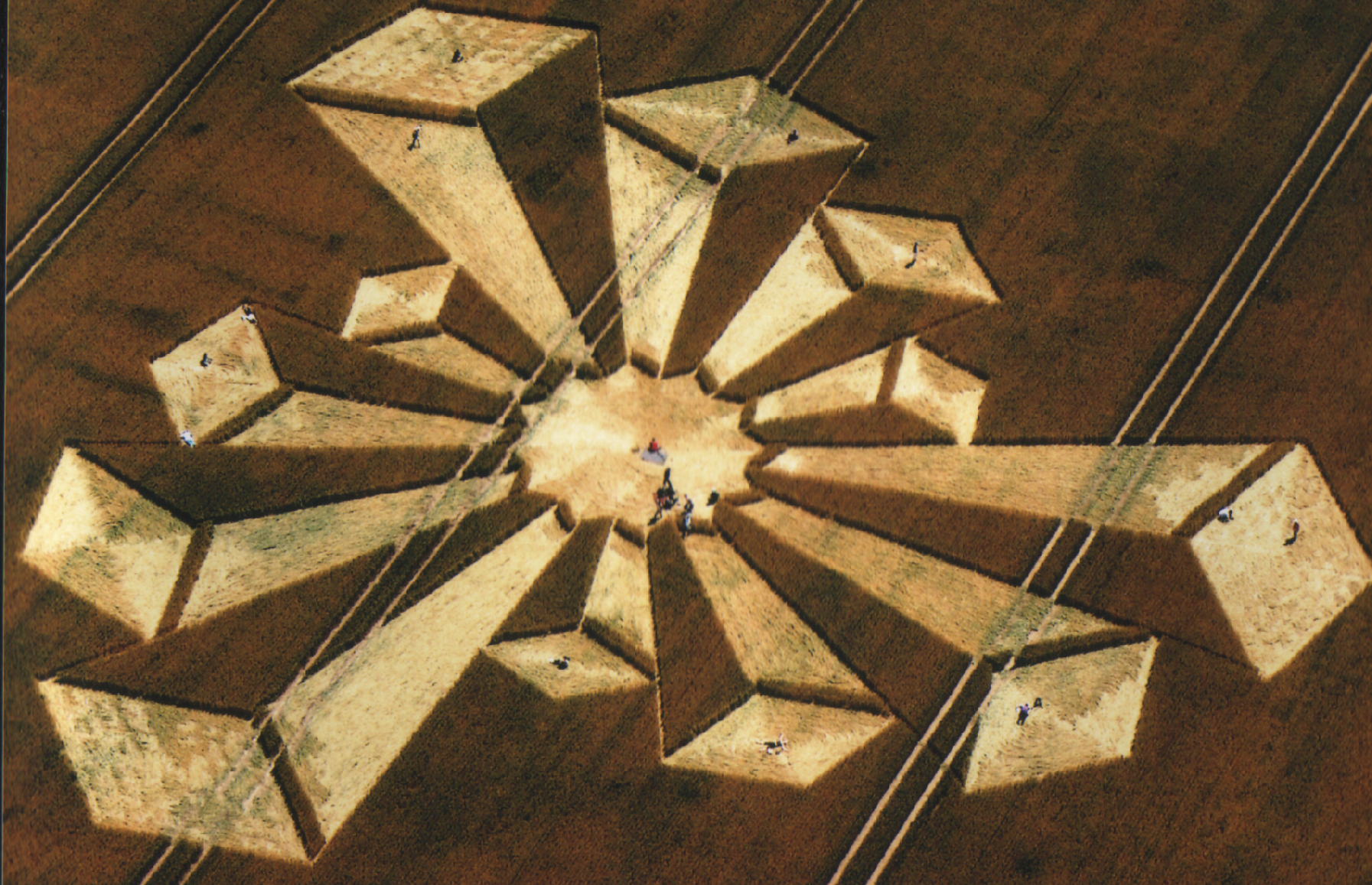

We sit at the hub of a distributed network. In the past, only some organizations sought to organize as networks – those that had to bring together, federate or otherwise affiliate disparate groups characterized by diversity. Today, an organization that does not distribute its functions is unlikely to leverage its network. Learning strategy therefore carefully considers how to decentralize the means while sharpening the aim.

How do we establish a mentoring relationship? What do we do when we identify a knowledge or performance gap in a colleague? This is a sensitive issue. Pointing to a gap is more likely to lead to a productive process when mutual trust is a pre-existing condition. When we mentor a colleague, we rely on our relationships as peers and our shared values. We deploy a range of context-specific approaches.

Mentor was the name of the adviser of the young Telemachus in Homer’s Odyssey . A mentor is an experienced and trusted advisor. In the workplace, mentoring usually involves providing counsel to colleagues. Mentoring relationships may be purely informal one-offs or imply a deeper investment for both mentor and mentee. For mentoring relationships to deepen and become sustainable requires mutual identification and recognition.

How do we get newcomers onboard? Onboarding refers to the mechanism through which new staff acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and behaviors to become effective “insiders” of the organization.

Fostering relationships that enable and sustain collaboration and inquiry requires building trust about both technical competencies and each person’s interest in dialogue. Therefore, two contexts require special attention. First, when newcomers come onboard to the team, they may or may not be familiar with the general organizational context or the specific working conditions.

Our areas of work are siloed due to limited resources and time, the huge scope of our global mandate, the high level of specialization required, and internal politics. Collaboration and learning as a team (beyond the unit level) requires leadership and concerted effort. It is hard to sustain over time. Yet, to collaborate we build, sustain and renew many individual relationships based on trust and need.

What do we do when we cannot achieve certainty? We increasingly accept that we need to make decisions without the comfort of certainty. It is okay to not know. It is healthy to accept the unknown as we no longer seek certainty. It is when we are no longer certain that we learn. In some cases, uncertainty opens the door to knowledge that we were not seeking. This is incidental learning. The organization still expects certainty.

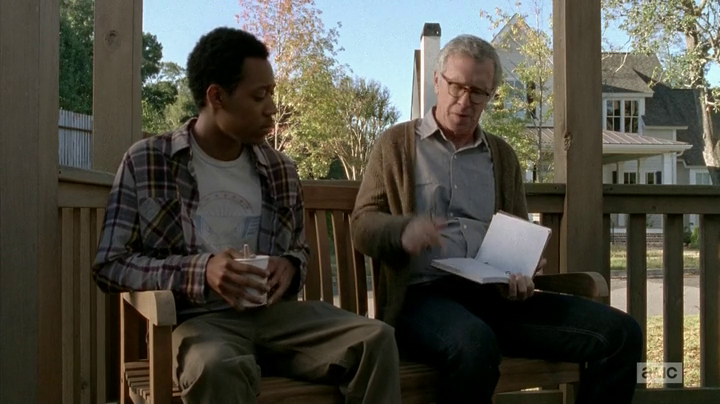

In this episode, the young Noah has asked to meet with Reg, an elderly architect or engineer who had the know-how to build the wall that protects the community of Alexandria, which some believe has survived zombies and other predators mostly by sheer luck. Noah recognizes that it’s more than luck – and wants to Reg to pass on knowledge and expertise that is different from that needed only to avert death.

How do we navigate these rules while achieving intended purpose? When we need new knowledge, where do we go? How do we go about it? How do we limit our exploration to ensure that we can still deliver on our tasks?