Back in 2017, I was asked to peer review an article and its author asked if I would like the review to be “open” – that is that my name would be shown as a reviewer; 10.1073/pnas.1709586114[/cite/] indeed it was!

Back in 2017, I was asked to peer review an article and its author asked if I would like the review to be “open” – that is that my name would be shown as a reviewer; 10.1073/pnas.1709586114[/cite/] indeed it was!

Metadata is something that goes on behind the scenes and is rarely of concern to either author or readers of scientific articles. Here I tell a story where it has rather greater exposure.

I should start by saying that the server on which this blog is posted was set up in June 1993. Although the physical object has been replaced a few times, and had been “virtualised” about 15 years ago, a small number of the underlying software base components may well date way back, perhaps even to 1993.

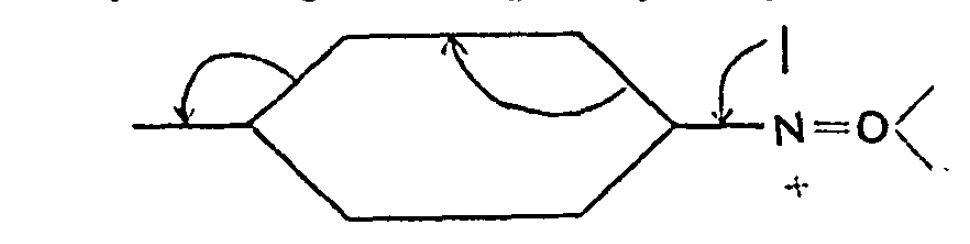

Chemists now use the term “curly arrows” as a language to describe the electronic rearrangements that occur when a (predominately organic) molecule transforms to another – the so called chemical reaction. It is also used to infer, via valence bond or resonance theory, what the mechanistic implications of that reaction are.

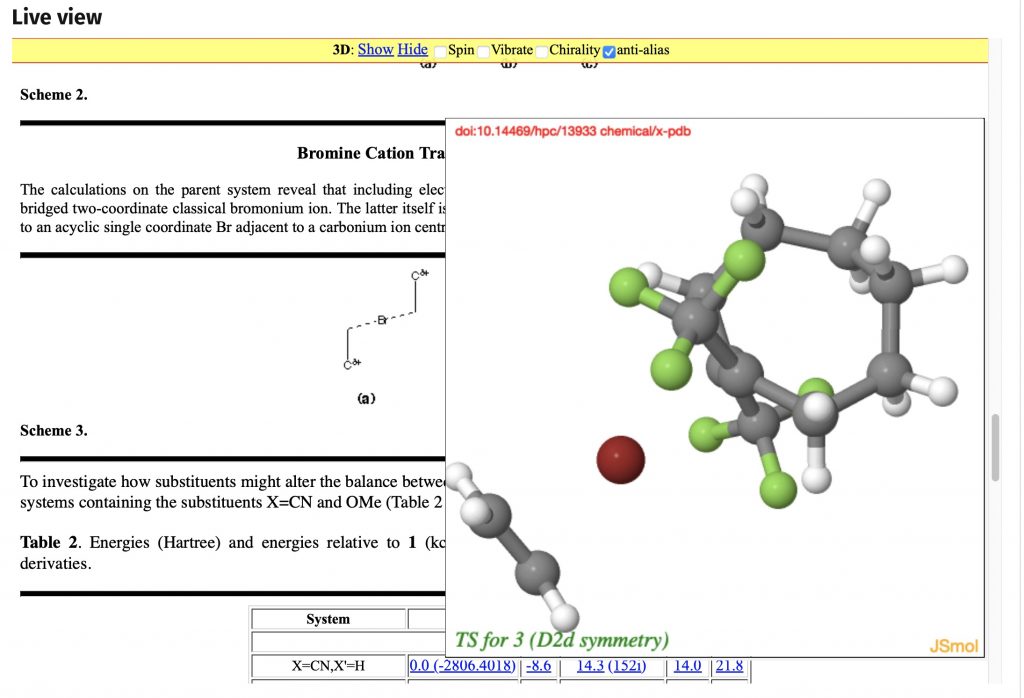

I can remember a time when journal articles carried selected data within their body as e.g. Tables, Figures or Experimental procedures, with the rest consigned to a box of paper deposited (for UK journals) at the British library. Then came ESI or electronic supporting information.

In the previous post, I explored the so-called “impossible” molecule methanetriol. It is regarded as such because the equilbrium resulting in loss of water is very facile, being exoenergic by ~14 kcal/mol in free energy. Here I explore whether changing the substituent R could result in suppressing the loss of water and stabilising the triol.

What constitutes an “impossible molecule”? Well, here are two, the first being the topic of a recent article. The second is a favourite of organic chemistry tutors, to see if their students recognise it as an unusual (= impossible) form of a much better known molecule.

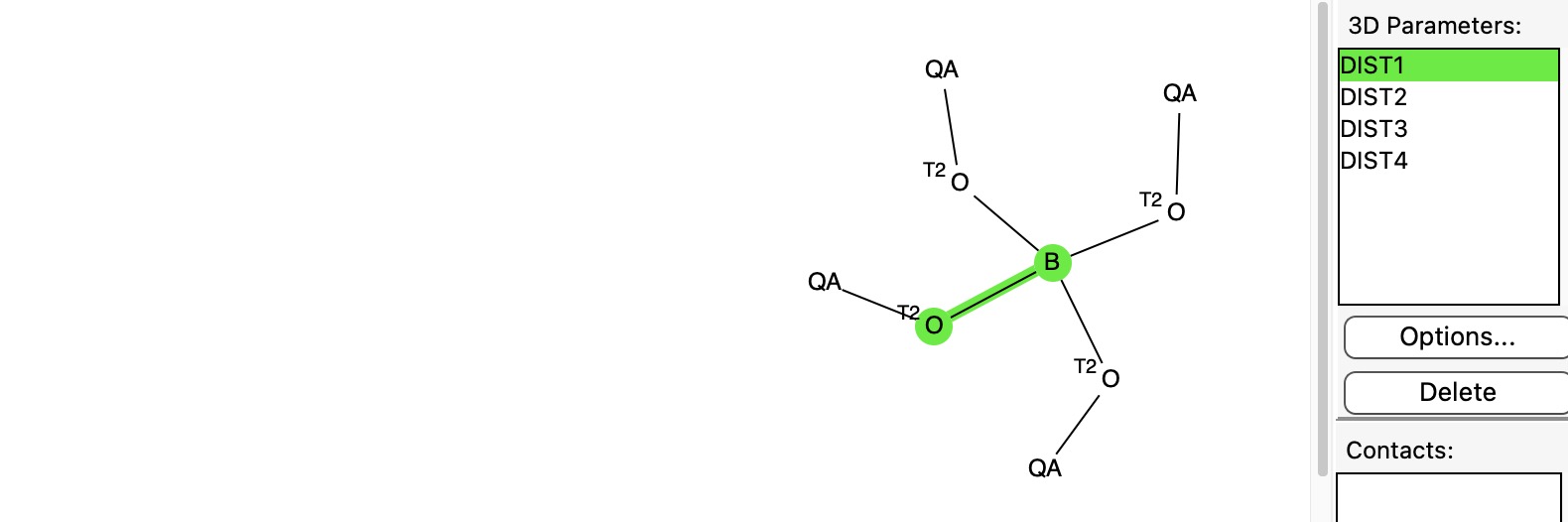

In an earlier post, I discussed a phenomenon known as the “anomeric effect” exhibited by tetrahedral carbon compounds with four C-O bonds. Each oxygen itself bears two bonds and has two lone pairs, and either of these can align with one of three other C-O bonds to generate an anomeric effect.

In the mid to late 1990s as the Web developed, it was becoming more obvious that one area it would revolutionise was of scholarly journal publishing. Since the days of the very first scientific journals in the 1650s, the medium had been firmly rooted in paper.

I have written a few times about the so-called “anomeric effect“, which relates to stereoelectronic interactions in molecules such as sugars bearing a tetrahedral carbon atom with at least two oxygen substituents.

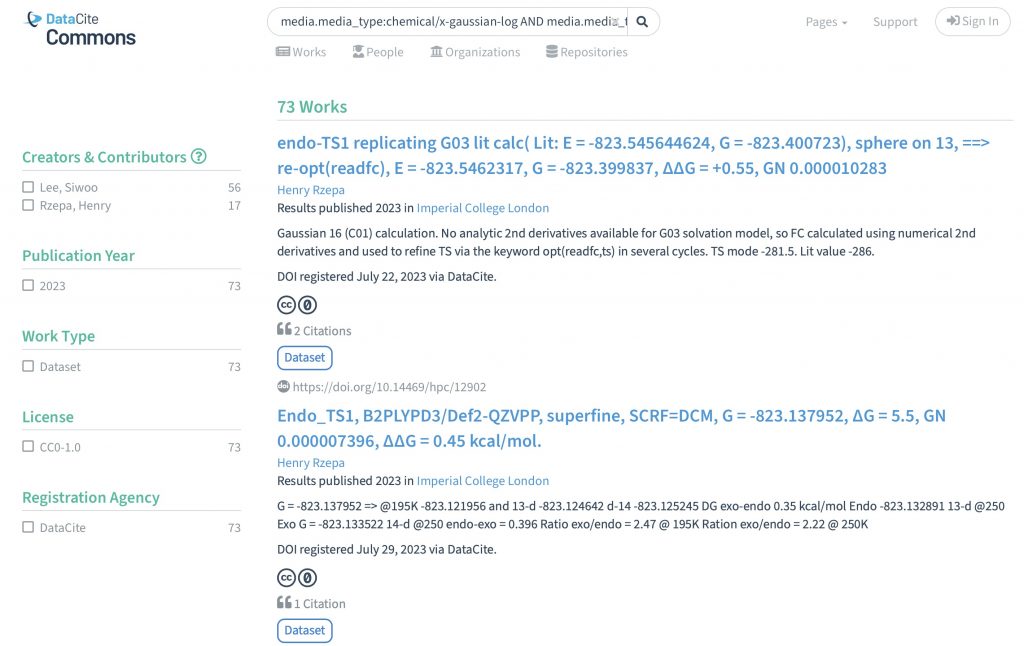

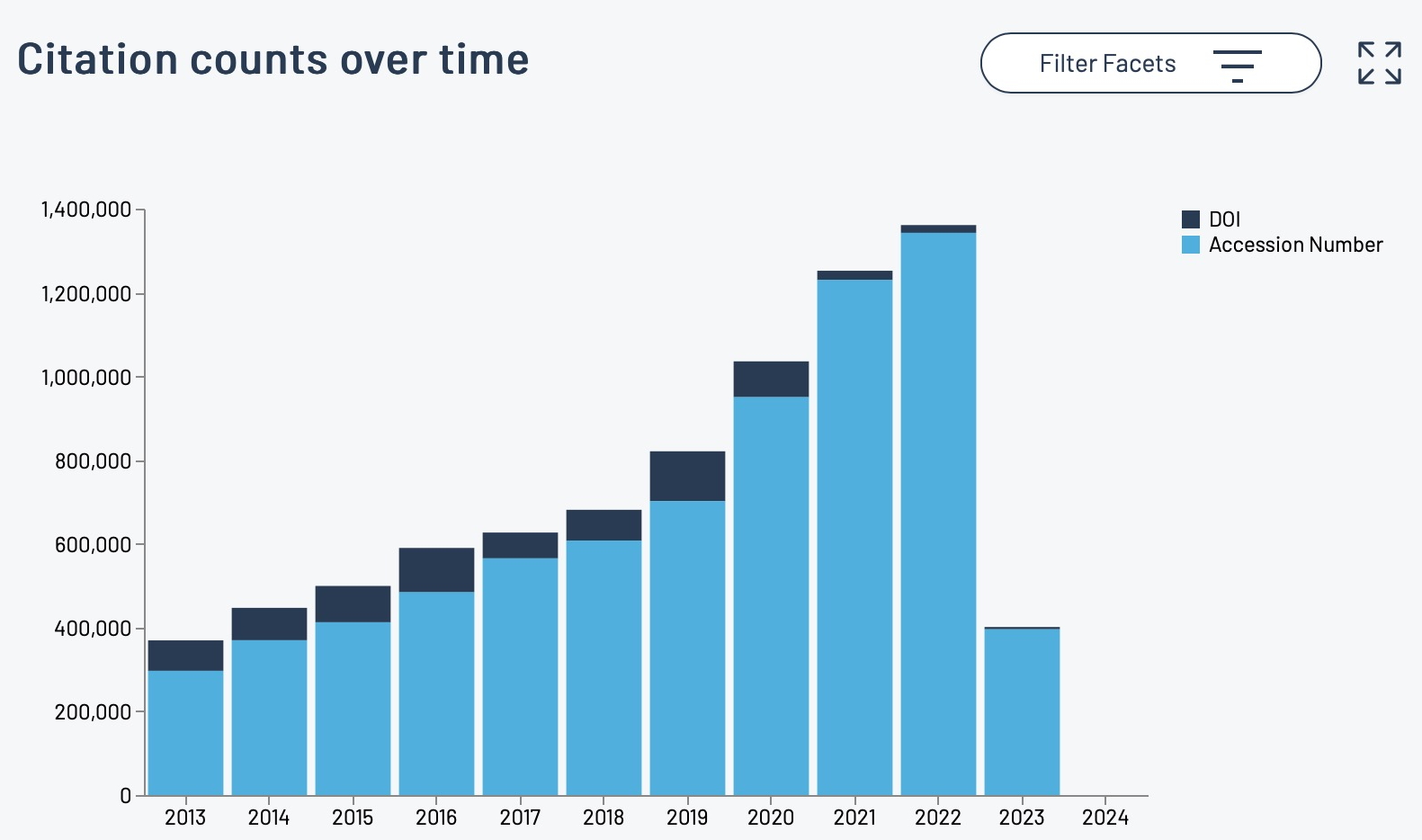

The recent release of the DataCite Data Citation corpus, which has the stated aim of providing “a trusted central aggregate of all data citations to further our understanding of data usage and advance meaningful data metrics” made me want to investigate what the current state of citing data in the area of chemistry might be. […]