This is an English translation of my original German contribution to the Merkur Blog in response to the contributions by Gehring and Tautz. “Scientific publishing” may sound like a minor rung in the ivory tower. It is not. The system […] ↓ Read the rest of this entry...

Rogue Scholar Beiträge

We held the first TESSERA hackathon over the Indian AI Impact summit in Delhi today, thanks to sponsorship from OpenUK.

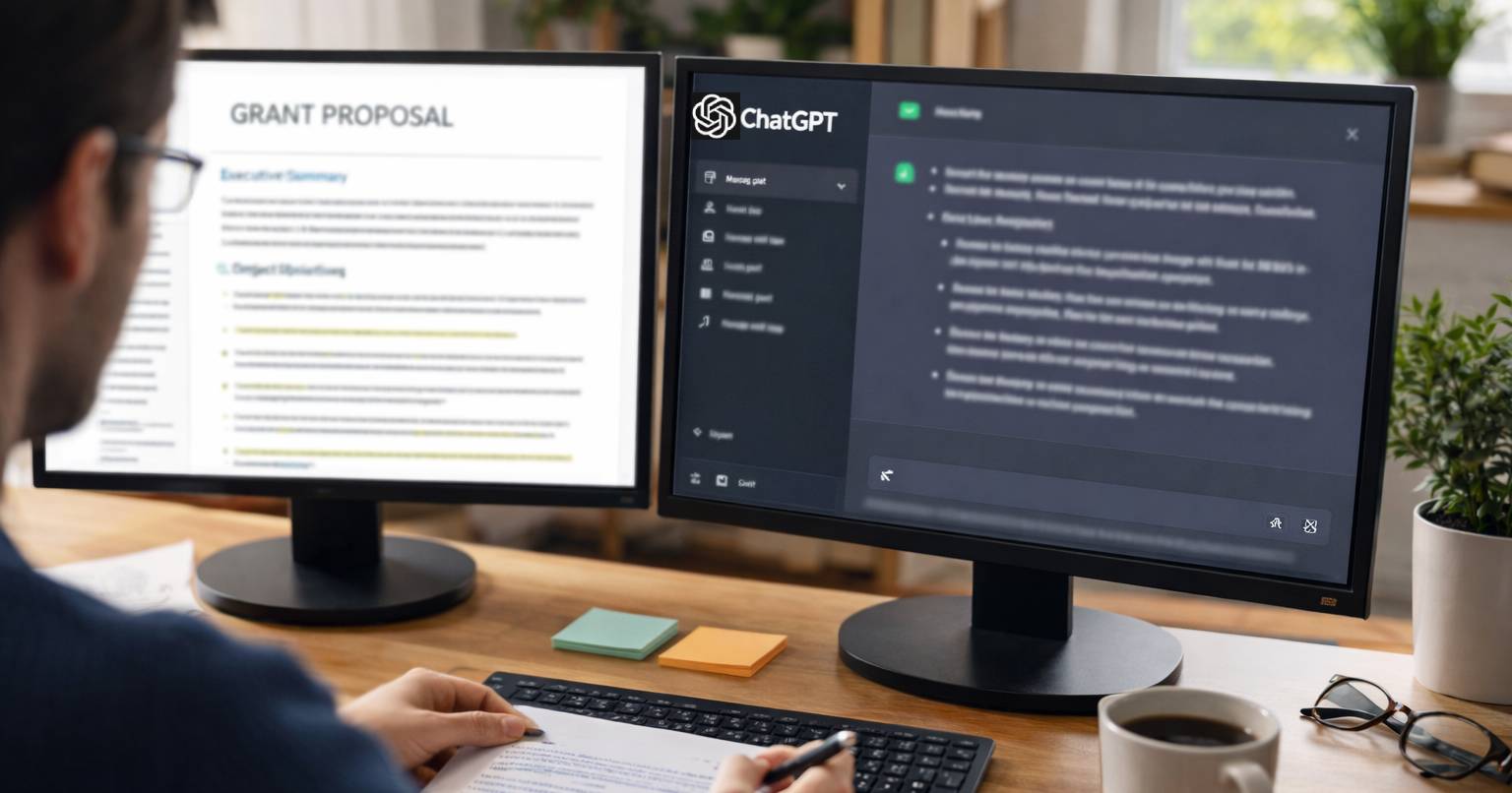

Responsibly using AI for a structured first pass manuscript / grant proposal review can reduce reviewer variance while keeping human judgment central. Bonus: a prompt I use for my own draft proposals.

I’m honoured to be giving a talk on Diamond Open Access at the 89th Annual Conference of the German Physical Society (Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft, DPG), specifically at the Spring Meeting of the Matter and Cosmos Section (SMuK). This invitation by the DPG, one of the largest physical societies in the world, is a great privilege, […]

A contribution to the United Nations Independent Scientific Panel on the Effects of Nuclear War

Nach dem Militärputsch in Myanmar/Burma im Jahr 2021 sehen sich Studierende und Lehrende der University of Yangon sowie anderer Bildungseinrichtungen erneut mit militärischer Gewalt, Unterdrückung, Inhaftierung und Krieg konfrontiert.

This month’s news includes: Research software community news, including Open Science NL’s €5.4 million award to the Netherlands eScience Center Funding opportunities, including the Software Sustainability Institute’s Research Software Maintenance Fund (RSMF) Round 2 Become a founding sponsor of IRSC26 Help shape the future of research software engineering in the age of generative AI Opportunities to get involved with community initiatives

Over a long weekend, between February 14-16, the 19th Tricota Cultural took place in Villa Ani Mi , a small village just north of where I’m currently living. As part of the local Carnaval celebrations in the Sierras Chicas, folks play music, dance and also celebrate with King Momo, represented by a big Papier-mâché effigy. This year, King Momo’s place was taken by Queen Moma though.

TW: stridently anti–Roman Catholic rhetoric, medieval realist metaphysics Popular histories of the Reformation typically emphasize the discontinuity between medieval theology and the Reformers.

Responsible-by-design reframes legitimacy as something that is earned continuously, not bestowed once

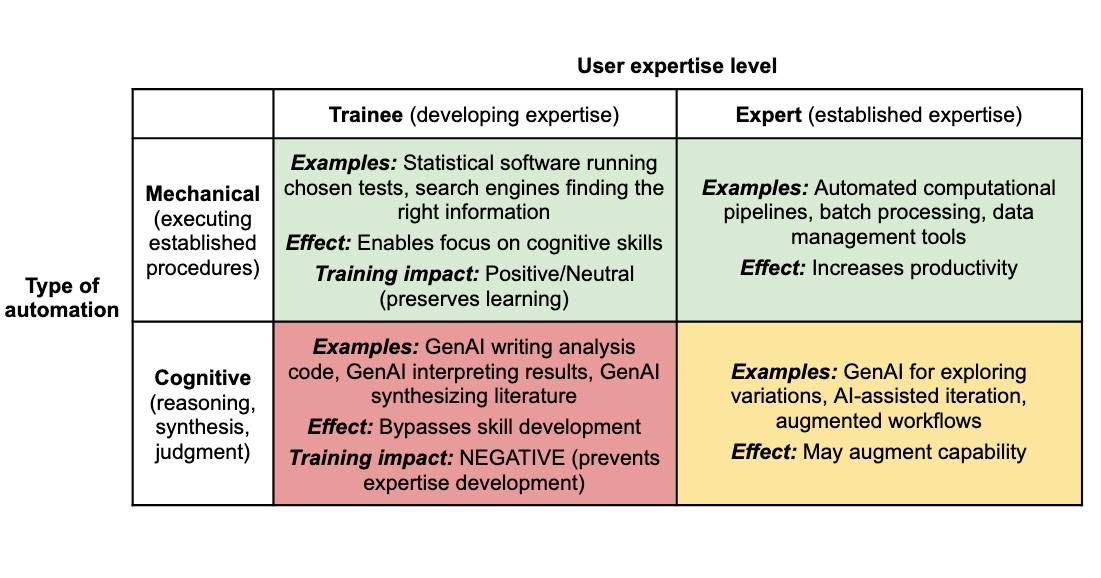

A developmental framework for sequencing AI use in PhD training