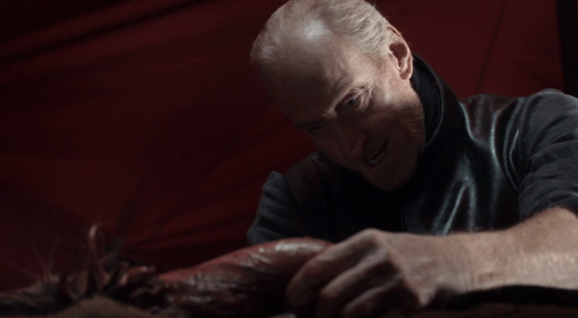

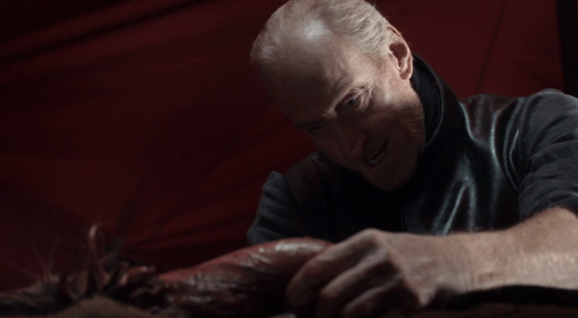

‘You Win or You Die’, the seventh episode from the first season of Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-present), contains a scene that has deservedly gathered attention and acclaim.

‘You Win or You Die’, the seventh episode from the first season of Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-present), contains a scene that has deservedly gathered attention and acclaim.

In a recent discussion about war on film and television (I probably steer discussions in this direction more often than my friends and family would like), a friend made the point that ‘war is war’. I have been thinking about this phrase a lot recently.

Last September, an interesting debate played out in the landscape of American media criticism.

The look of the stylish British spy and detective shows, filmed in colour in the 1960s, results from where and how they were made, and pop sensation Cliff Richard had a lot to do with it. The musical The Young Ones (d. Sidney J. Furie), starring Cliff, was shot at Elstree Studios near London in 1961, and a quite extensive backlot town was built for the film.

The 25 th of January 2015, the day of the parliamentary elections in Greece, was characterised as a historical turning point for the country after the leftwing radical party SYRIZA swept into power.

Cathy Johnson and Karen Boyle’s recent blog posts on Working Ourselves and Others to Death have generated an animated and, in my eyes, helpful debate that has also allowed me to take stock on where some of my colleagues and myself are in terms of our working patterns.

We’re fortunate in television studies. The exclusively formal, stylistic, and ideological attention paid to texts in literary studies has never been deemed sufficient in our field—the immensely social nature of TV, like cinema, has largely militated against such reductionism. Endless moral panics about learning, lust, and lawlessness have meant that technologies, audiences, and regulations have been necessary components of our agenda.

(A re-introduction to the Eye tracking the Moving Image Research Group) ** *** * I have a painterly confession to make. When I saw eye tracking visualisations for the first time they flooded me with affecting impressions.

To write his television serial Foyle’s War (2002–2015), Anthony Horowitz armed himself with history. Spinning tales based on actual events in England during and a couple of years after World War II, he reminds us that life is the best friend fiction ever had.

There have been few DVD box sets that I have enjoyed going through so much as volumes 2-4 of the Network Look-Back on 70’s Telly anthologies, which collectively run to 48 different half-hour shows, allowing the viewer investigate almost the full range of 1970s ITV children’s drama (Volume 1 is devoted to pre-school shows). They really do seem to have everything in them, the only omissions that I can find being anything made by Southern,

I am on a big search – and it will be a long and protracted search – for a new meaning. Not of life (well, that as well, but that’ll last even longer), but of what it means to watch television. Yes, I have discovered doubt: I no longer trust my old instincts. And so I will spend 2015 – this is at least one of my new year’s resolutions – on thinking through what it means to watch television today.