I took a pistol course in undergrad, and while I was a poor marksman I enjoyed the experience. In particular, I was surprised by how meditative the act of shooting was. As our instructor explained, much of good shooting comes down to not doing anything when you pull the trigger.

Corin Wagen

“Like arrows in the hand of a warrior are the children of one's youth.” –Psalm 127:4 What if our most fundamental assumptions about parenting were wrong? That’s the question that Michaeleen Doucleff’s 2021 book Hunt, Gather, Parent tries to tackle.

Quantum computing gets a lot of attention these days. In this post, I want to examine the application of quantum computing to quantum chemistry, with a focus on determining whether there are any business-viable applications today.

In 2019, ChemistryWorld published a “wish list” of reactions for organic chemistry, describing five hypothetical reactions which were particularly desirable for medicinal chemistry. A few recent papers brought this back to my mind, so I revisited the list with the aim of seeing what progress had been made.

(in the spirit of Dale Carnegie and post-rat etiquette guides) Scientists, engineers, and other technical people often make fun of networking. Until a few years ago, I did this too: I thought networking was some dumb activity done by business students who didn’t have actual work to do, or something exploitative focused on pure self-advancement.

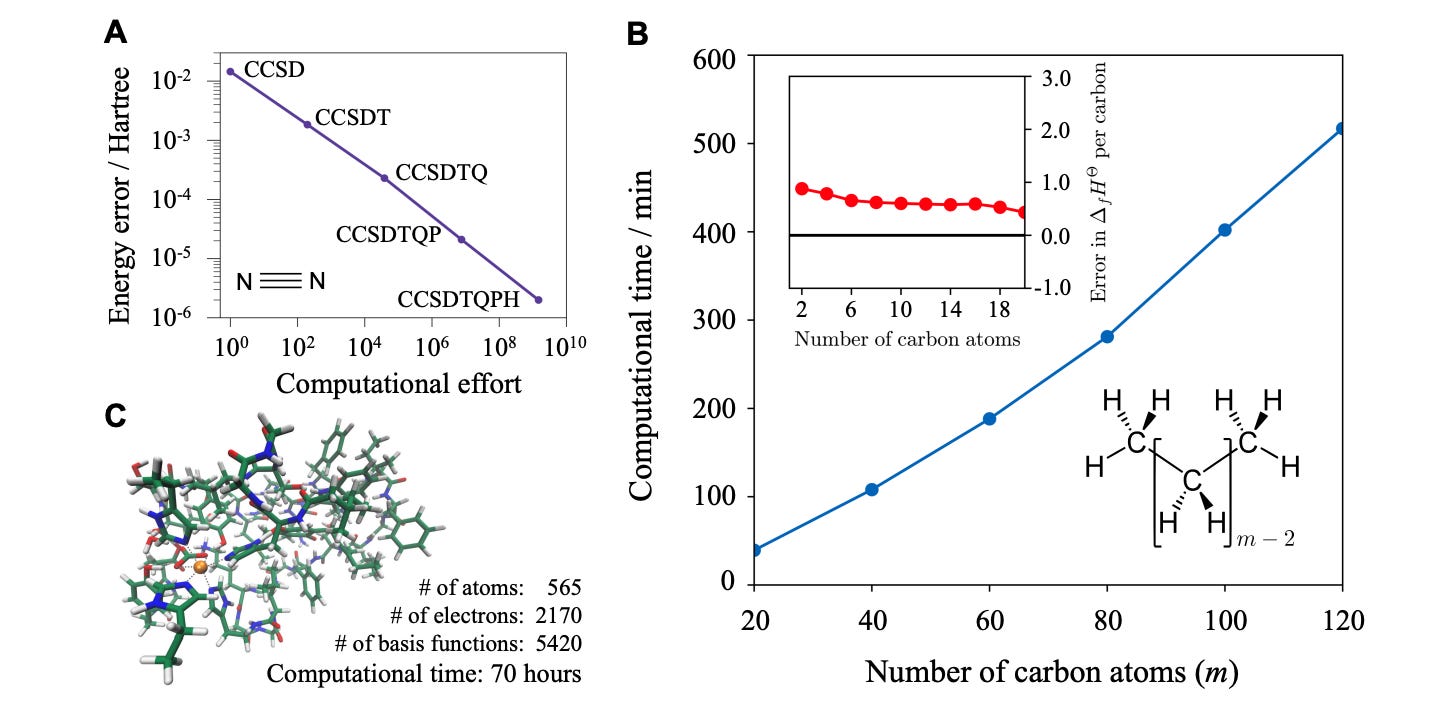

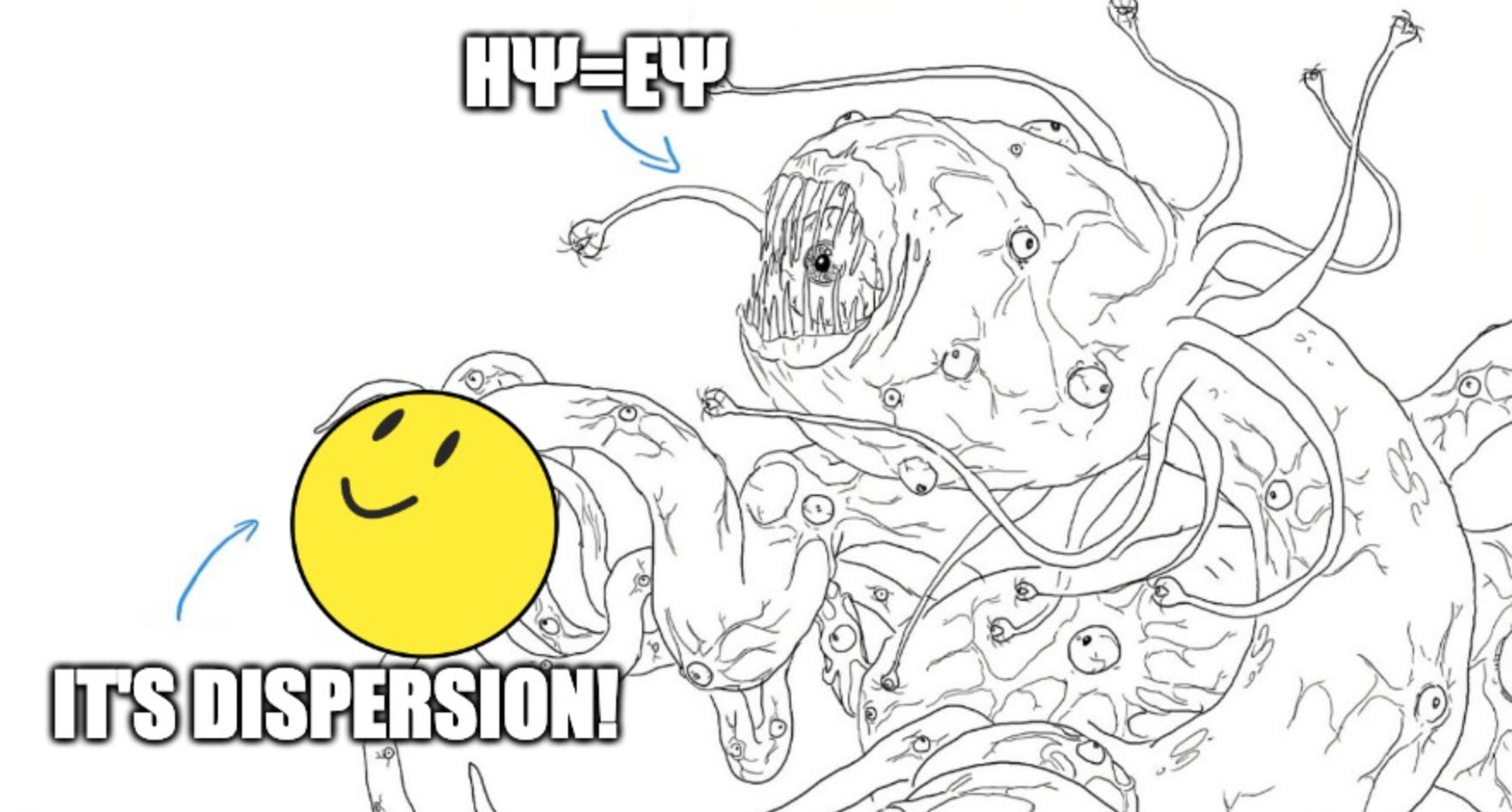

“A cord of three strands is not easily broken.” —Ecclesiastes 4:12 Computational chemistry, like all attempts to simulate reality, is defined by tradeoffs. Reality is far too complex to simulate perfectly, and so scientists have developed a plethora of approximations, each of which reduces both the cost (i.e. time) and the accuracy of the simulation.

ICYMI: Ari and I announced our new company, Rowan! We wrote an article about what we're hoping to build, which you can read here. Also, this blog is now listed on The Rogue Scholar, meaning that posts have DOIs and can be easily cited. Conventional quantum chemical computations operate on a collection of atoms and create a single wavefunction for the entire system, with an associated energy and possibly other properties.

The Pauling model for enzymatic catalysis states that enzymes are “antibodies for the transition state”—in other words, they preferentially bind to the transition state of a given reaction, rather than the reactants or products. This binding interaction stabilizes the TS, thus lowering its energy and accelerating the reaction.

Since the ostensible purpose of organic methodology is to develop reactions that are useful in the real world, the utility of a method is in large part dictated by the accessibility of the starting materials.

An important problem with simulating chemical reactions is that reactions generally take place in solvent, but most simulations are run without solvent molecules. This is a big deal, since much of the inaccuracy associated with simulation actually stems from poor treatment of solvation: when gas phase experimental data is compared to computations, the results are often quite good.