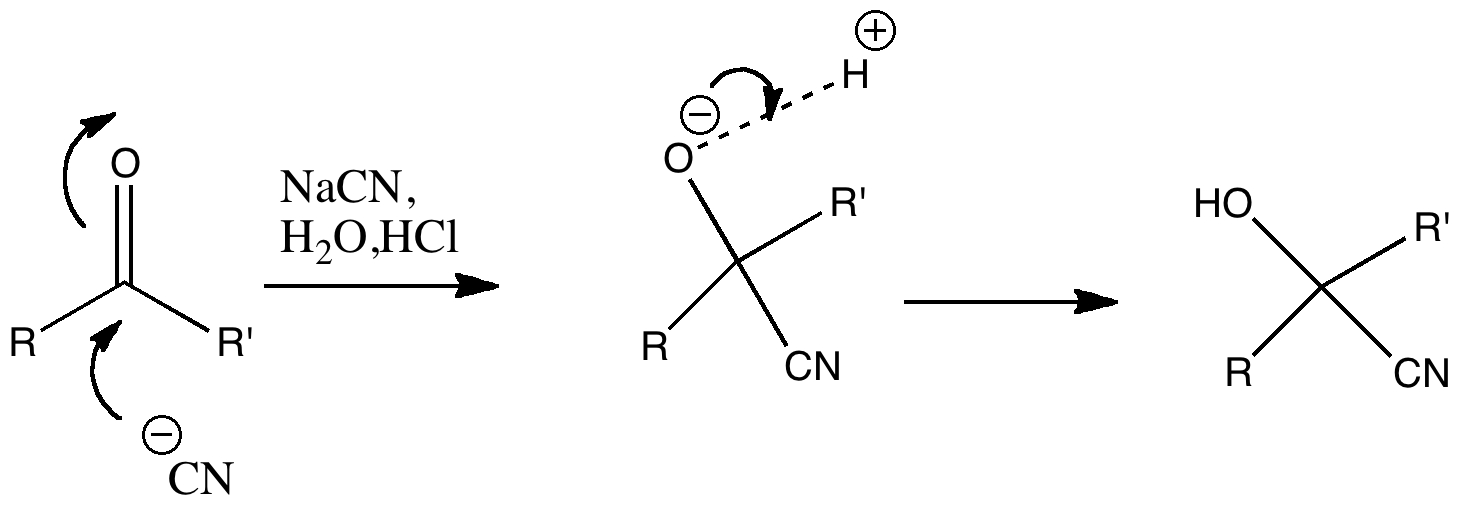

Nucleophilic addition of cyanide to a ketone or aldehyde is a standard reaction for introductory organic chemistry. But is all as it seems? The reaction is often represented as below, and this seems simple enough.

Nucleophilic addition of cyanide to a ketone or aldehyde is a standard reaction for introductory organic chemistry. But is all as it seems? The reaction is often represented as below, and this seems simple enough.

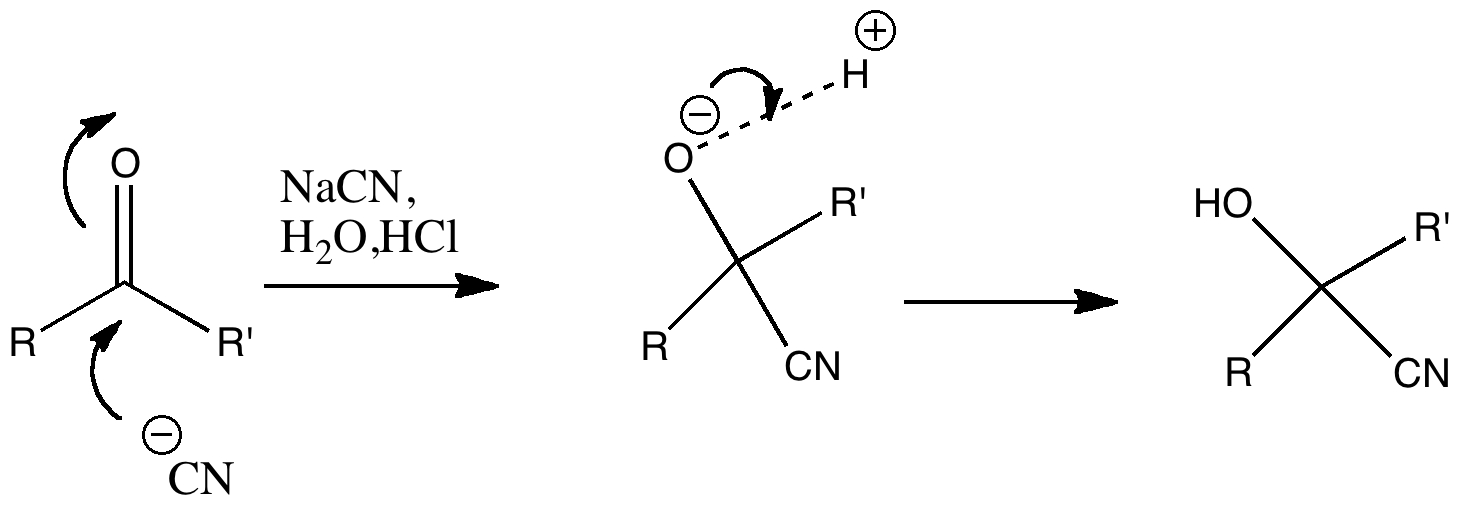

Much like chocolate, some of us metallaholics cannot get enough. So WUQXIP proved an irresistible frolic (DOI: 10.1021/om020789h). Let us start with benzene. It can have metals added in two ways, whilst preserving its essential aromaticity.

One of my chemical heroes is William Perkin, who in 1856 famously (and accidentally) made the dye mauveine as an 18 year old whilst a student of August von Hofmann, the founder of the Royal College of Chemistry (at what is now Imperial College London). Perkin went on to found the British synthetic dyestuffs and perfumeries industries.

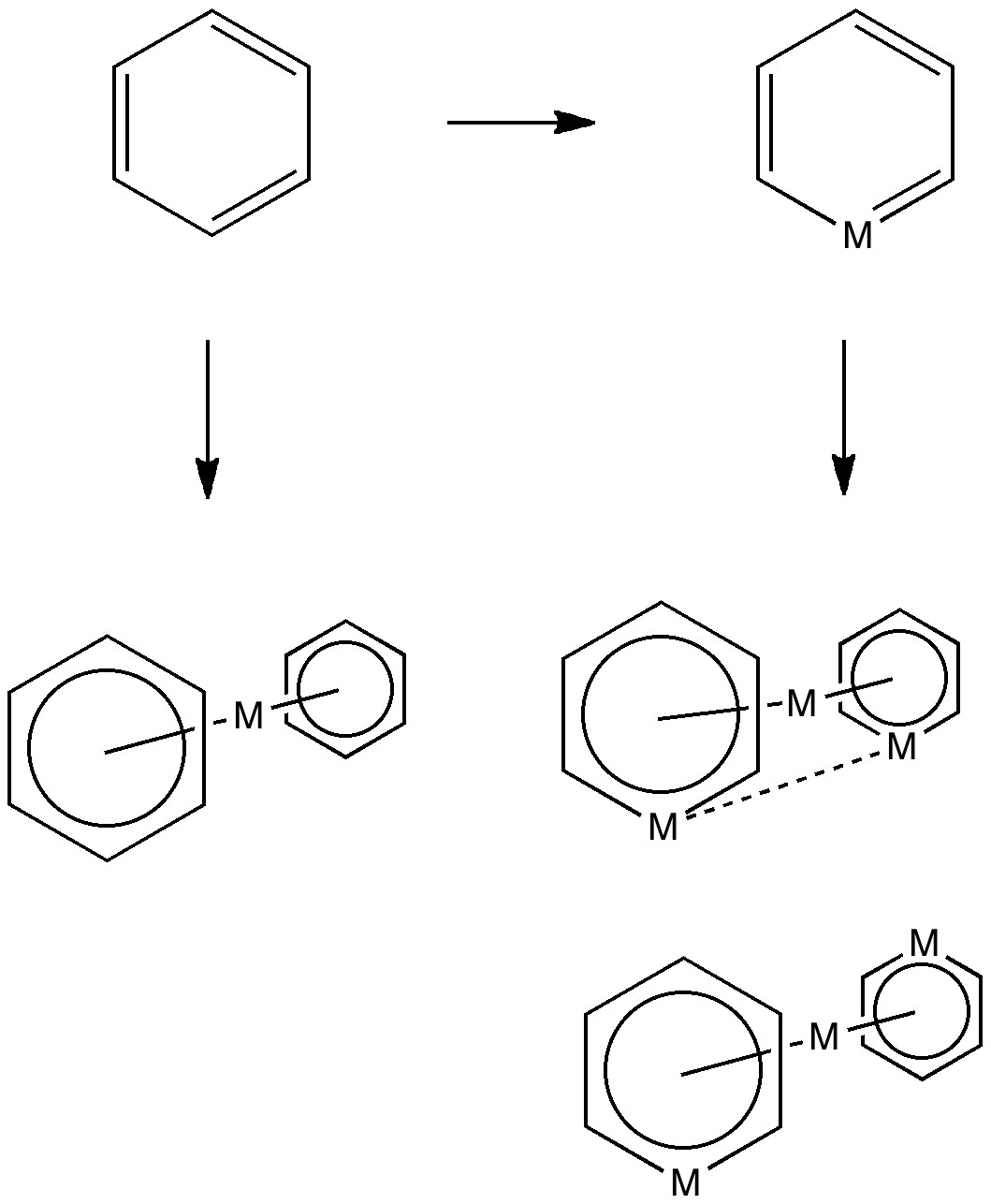

The Möbius band is an experimental delight. In its original forms, it came flat-packed as below.

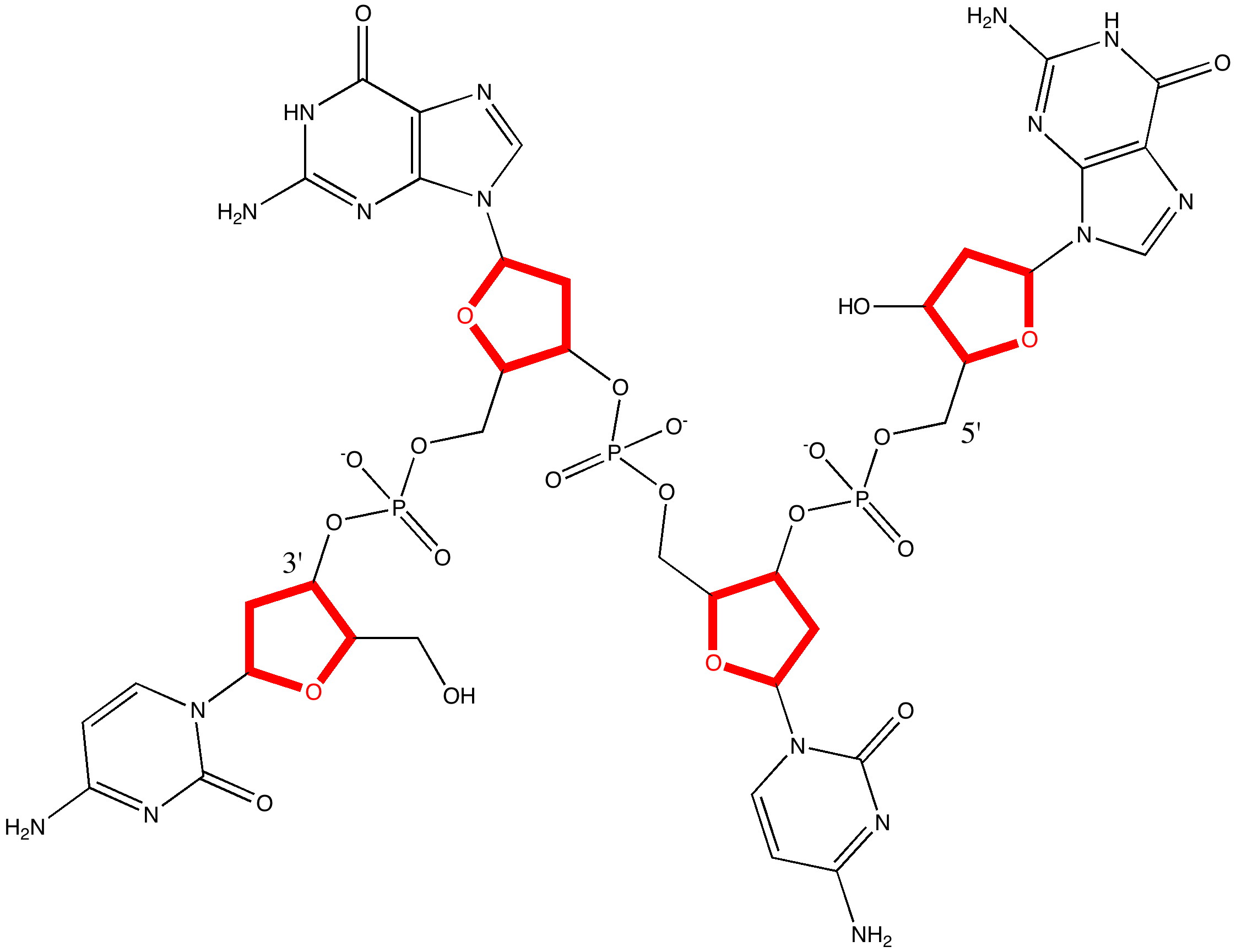

In 1953, the model of the DNA molecule led to what has become regarded as the most famous scientific diagram of the 20th century.

Much of chemistry is about bonds, but sometimes it can also be about anti-bonds. It is also true that the simplest of molecules can have quite subtle properties. Thus most undergraduate courses in chemistry deal with how to describe the bonding in the diatomics of the first row of the periodic table.

In my blogroll, I link to Tim Gowers’ blog. He is a very eminent mathematician, and so it is interesting to see what motivates him to write a blog about mathematics. This latest post goes a large way to explaining why.

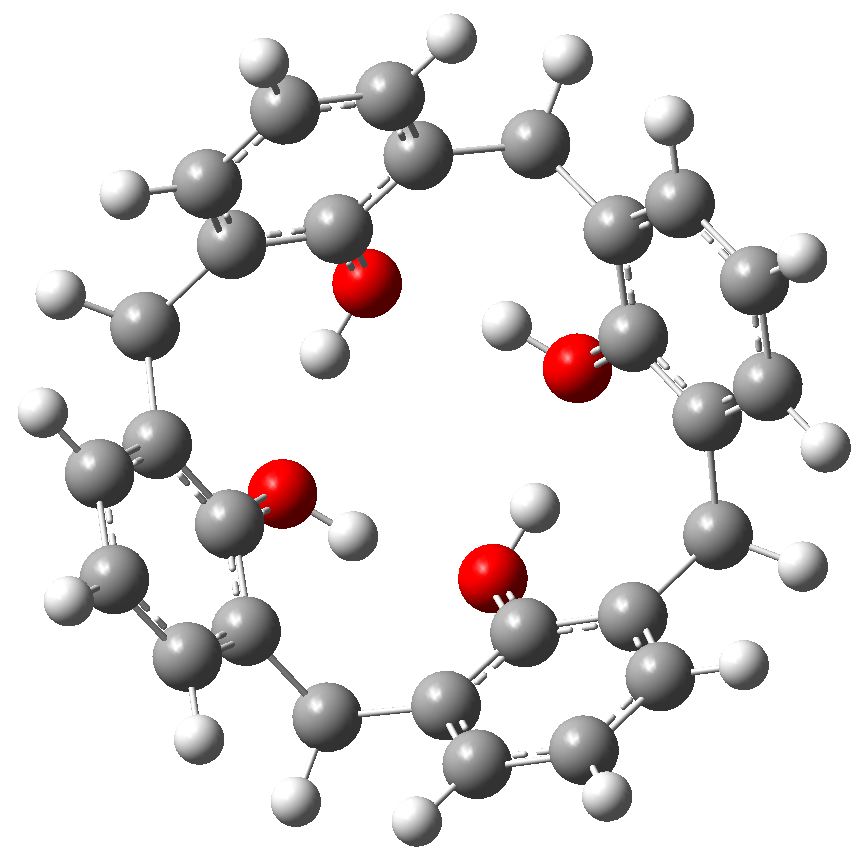

This story starts with a calixarene, a molecule (suitably adorned with substituents) frequently used as a host to entrap a guest and perchance make the guest do something interesting. Such a calixarene was at the heart of a recent story where an attempt was made to induce it to capture cyclobutadiene in its cavity.

When Watson and Crick (WC) constructed their famous 3D model for DNA, they had to decide whether to make the double helix left or right handed.

One of the delights of wandering around an undergraduate chemistry laboratory is discussing the unexpected, if not the outright impossible, with students. The >100% yield in a reaction is an example.

Science is about making connections. Plenty are on show in Watson and Crick’s famous 1953 article on the structure of DNA but often with the tersest of explanations. Take for example their statement “Both chains follow right-handed helices“. Where did that come from?