This piece is noticeably longer (twice the length) than the others on this Substack.

This piece is noticeably longer (twice the length) than the others on this Substack.

Hey Team! As you know, a lot of what I do is outline the details of how scientific systems and research institutes of the past worked. Tomorrow, I’ll be taking my first step in doing this kind of profile with one of the present, well-known, new science orgs! I’ll be spending a week on the ground (as well as more time in the coming months) at the lab interviewing, observing, etc. I already have a list of things I plan on looking into.

Subscribe now I’ve finally updated the “About” section of this Substack. For months and months, I put it off because I was so busy working a job and writing at night. Then, I began writing full-time and concerned myself wholly with making sure I kept up producing novel pieces as a “professional.” Today, I finally got to it. And I realized this was the perfect opportunity to do something I’ve never done: a subscriber push.

I just finished Warren Weaver’s ludicrously underrated autobiography, Scene of Change: A Lifetime in American Science (It’s so out of print that the only copies I could even find were $80+ and they were few and far between) . I’m working on a long-form post about some major takeaways from the book, but, in the meantime, I couldn’t resist releasing a Short covering a few other interesting pieces of the book.

Erik Hoel, who writes The Intrinsic Perspective, has just announced that he is leaving his position at Tufts to pursue Substack writing. If that name does not ring a bell, readers of this Substack may know him as the “guy who wrote the Why we stopped making Einsteins piece” on aristocratic tutoring. Hoel is a great thinker who integrates fields seamlessly, and that’s part of the reason he chose to leave academia.

In this ‘Short’ I’ll share a few excerpts from Feynman’s oral history that give readers an idea of:

This Substack was largely born out of me sitting on a mountain of fun facts about early 1900s science and the economics of innovation. Some of that, less than 10%, makes it into the longer pieces which make quite coherent, fleshed-out points. But, sometimes, there’s just a fun quote or graph that can stand alone that I think you all would get a kick out of. To this point, sadly, I’ve been leaving these fun tidbits out of the Substack altogether.

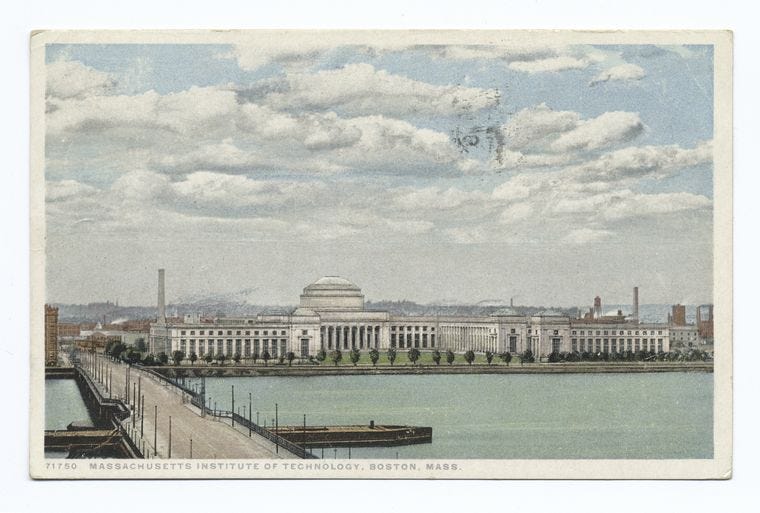

To this point, I’ve written tens of thousands of words on this Substack covering the work of scientists from the early-to-mid-1900s — a golden era of American science and innovation — in a familiar setting: the university.

If you’re interested in the structure of scientific institutions, we’re living through remarkably exciting times. This past week I was corresponding with Gerald Holton, whose 1952 work I covered in my piece When do ideas get easier to find?. Holton, now 100 years old, is obviously spending less time actively working and keeping up with the fields in which he was prolific in his heyday.

Each piece in the MIT series can stand alone for the most part, but I’ve written them in such a way that they build off each other.

Each piece in the MIT series can stand alone for the most part, but I’ve written them in such a way that they build off each other.