Listen in on the Foundation’s first invitation-only Clubhouse chat. Karen Watkins and I chatted about the Foundation’s unique approach to this triptych of learning, leadership, and impact in the Digital Age. We shared some of the insights we gained about resilience during the first year of COVID-19, learning from the Foundation’s immunization programme that connected thousands of health professionals during the early days of the pandemic.

Reda Sadki

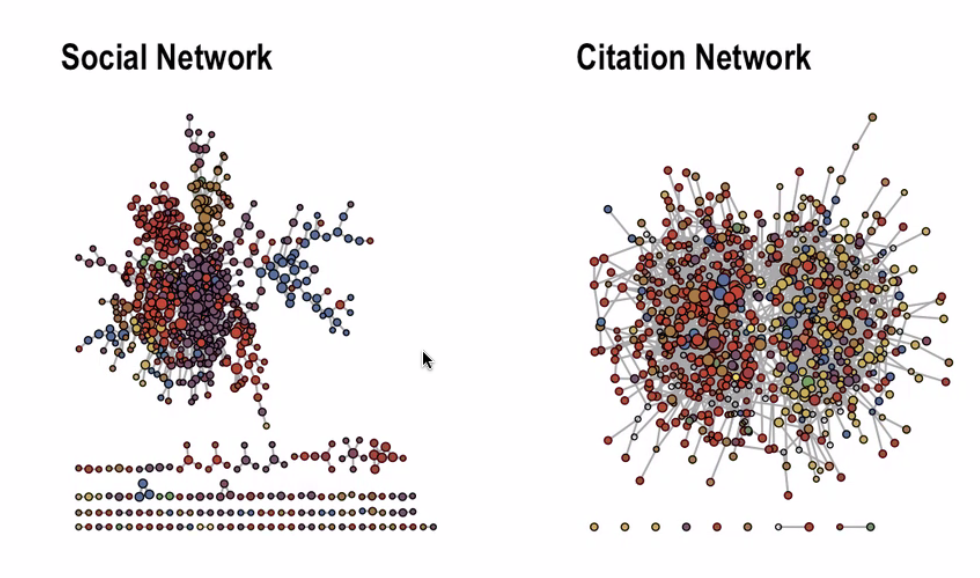

In July 2019, barely six months before the pandemic, we worked with alumni of The Geneva Learning Foundation’s immunization programme to build the Impact Accelerator in 86 countries. This global community of action for national and sub-national immunization staff pledged, following completion of one of the Foundation’s courses, to support each other in other to achieve impact.

We are launching a new Scholar programme about environmental threats to health, with an initial focus on radiation. (I mapped out what this might look like in 2017.) As part of the launch, we are enlisting support of immunization colleagues. Our immunization programme is our largest and most advanced programme, and still growing fast since its inception in 2016.

We understand the yearning to find a low-cost or no-cost way to spontaneously create a thriving community of practice in which participants engage intensively, volunteer undue amounts of time and effort to keeping the community alive, support other members, and make use of the resources and sharing that emerge.

Busy managers may enjoy connecting socially and exchanging informally with their peers. However, they are likely to find it difficult to justify time doing so. They may say “I’m too busy” but what they usually mean is that the opportunity cost is too high. The Achilles heel of communities of practice is that – just like formal training – they require managers to stop work in order to learn. They break the flow of learning in work.

If it keeps on rainin’, levee’s goin’ to break. When the levee breaks, I’ll have no place to stay. – Led Zeppelin While the International Trainer lands at the airport, is chauffeured to her hotel, and dutifully reviews her slides and prepares her materials, a literally and figuratively captive audience has been herded at great cost to that same hotel, lured in by a perverse combination of incentives.

ADELAIDE, 27 November 2020 (University of South Australia) – More than 80 million children under the age of one at risk of vaccine-preventable diseases. UniSA researchers are evaluating a new vaccination education initiative – the COVID-19 Peer Hub – to help immunisation and public health professionals tackle the emerging dangers of vaccine hesitancy amid the pandemic.

How we respond to the threat of a disaster is critical. Organizations planning physical-world events have a choice: You can cancel or postpone your event OR You can go digital . Why not go digital? You think it cannot be done. You do not know how to do it. You believe the experience will be inferior. It can be done. You can learn.

“Please, I need someone to enlighten me on the pros and cons of online courses for active learning and professional development.” There is quite a bit of contextual information missing to decode what is really being asked. We only know that it is an individual professional from an anglophone country in Africa. Still, I can think of at least three ways to answer this question. Answer #1. Wrong question.

L&D is dead. Pushing us down the blind alley of technological solutionism, the learning technologists have demoted learning to tool selection. Microlearning reduces the obsession with knowledge acquisition from a one-hour video to 60 one-minute videos. Gamification is lipstick on the pig of behaviorism. xAPI and other “X”-buzzwords are just the latest tin con by desperate LMS vendors.

Business gets done by groups in workshops and meetings and by individuals in private conversation. There is an undeniable cultural advantage for diplomacy that comes from looking your interlocutor in the eye. Emerging digital platforms are in the margins of this business. The pioneers are creaky in their infrastructure and, ironically, playing catch-up. They have long lost the initial burst of enthusiasm that led to their creation.