I mentioned in my last post an unjustly neglected paper from that golden age of 1951-1953 by Kirkwood and co. They had shown that Fischer’s famous guess for the absolute configurations of organic chiral molecules was correct. The two molecules used to infer this are shown below.

I wrote in an earlier post how Pauling’s Nobel prize-winning suggestion in February 1951 of a (left-handed) α-helical structure for proteins was based on the wrong absolute configuration of the amino acids (hence his helix should really have been the right-handed enantiomer). This was most famously established a few months later by Bijvoet’s definitive crystallographic determination of the […]

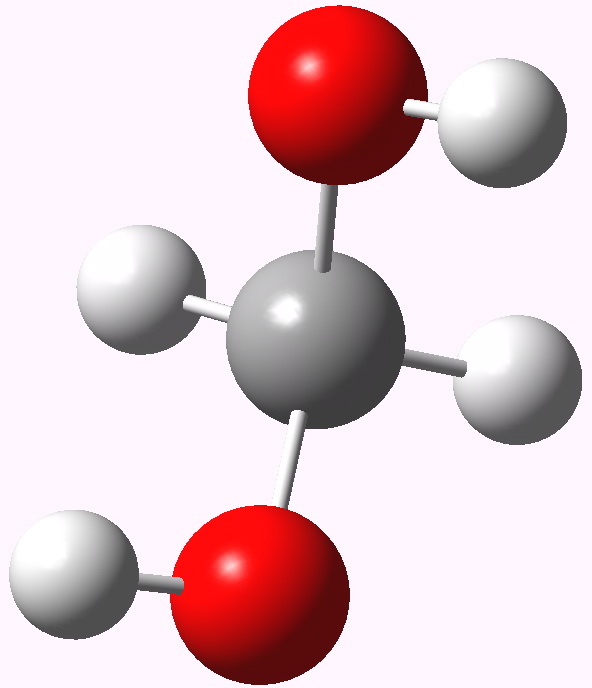

In my previous post I speculated why bis(trifluoromethyl) ketone tends to fully form a hydrate when dissolved in water, but acetone does not. Here I turn to asking why formaldehyde is also 80% converted to methanediol in water? Could it be that again, the diol is somehow preferentially stabilised compared to the carbonyl precursor and if so, why?

The equilibrium for the hydration of a ketone to form a gem-diol hydrate is known to be highly sensitive to substituents.

Sometimes, as a break from describing chemistry, I take to describing the (chemical/scientific) creations behind the (WordPress) blog system. It is fascinating how there do seem increasing signs of convergence between the blog post and the journal article.

One thing almost always leads to another in chemistry. In the last post, I described how an antiperiplanar migration could compete with an antiperiplanar elimination. This leads to the hydroboration-oxidation mechanism, the discovery of which resulted in Herbert C. Brown (at least in part) being awarded the Nobel prize in 1979.

The anti-periplanar principle permeates organic reactivity. Here I pick up on an example of the antiperiplanar E2 elimination (below, blue) by comparing it to a competing reaction involving a [1,2] antiperiplanar migration (red).

The previous post explored why E2 elimination reactions occur with an antiperiplanar geometry for the transition state. Here I have tweaked the initial reactant to make the overall reaction exothermic rather than endothermic as it was before. The change is startling.

The so-called E2 elimination mechanism is another one of those mainstays of organic chemistry. It is important because it introduces the principle that anti-periplanarity of the reacting atoms is favoured over other orientations such as the syn-periplanar form; Barton used this principle to great effect in developing the theory of conformational analysis.

In the previous post, I went over how a reaction can be stripped down to basic components. That exercise was essentially a flat one in two dimensions, establishing only what connections between atoms are made or broken. Here we look at the three dimensional arrangements.

Its a bit like a jigsaw puzzle in reverse, finding out to disassemble a chemical reaction into the pieces it is made from, and learning the rules that such reaction jigsaws follow. The following takes about 45-50 minutes to follow through with a group of students.