Thus famously wrote Woodward and Hoffmann (WH) in their classic monograph about the conservation of orbital symmetry in pericyclic reactions.

Previously, I had noted that Corey reported in 1963/65 the total synthesis of the sesquiterpene dihydrocostunolide. Compound 16, known as Eudesma-1,3-dien-6,13-olide was represented as shown below in black; the hydrogen shown in red was implicit in Corey’s representation, as was its stereochemistry. As of this instant, this compound is just one of 64,688,893 molecules recorded by Chemical Abstracts.

My previous three posts set out my take on three principle categories of pericyclic reaction. Here I tell a prequel to the understanding of these reactions.

Another common type of pericyclic reaction is the migration of hydrogen or carbon along a conjugated chain, as in the [1,3] migration of a carbon as shown below. As before, I explore the stereochemistry of the thermal and photochemical reactions.

The π 2 + π 2 cyclodimerisation of cis -butene is the simplest cycloaddition reaction with stereochemical implications. I here give it the same treatment as I did previously for electrocyclic pericyclic reactions. The photochemical reaction is known to give a mixture of two tetramethylcyclobutanes in the ratio of 1.3:1.0, with the all- cis isomer apparently predominating.

Woodward and Hoffmann published their milestone article “Stereochemistry of Electrocyclic Reactions” in 1965. This brought maturity to the electronic theory of organic chemistry, arguably started by the proto-theory of Armstrong some 75 years earlier. Here, I take a modern look at the archetypal carrier of this insight, the ring opening of dimethylcyclobutene.

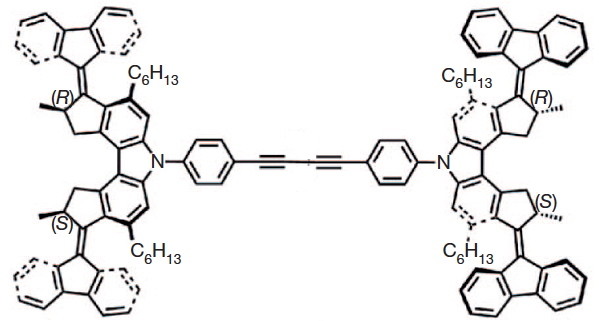

In the previous post, I wrote about the processes that might be involved in a molecular wheel rotating. A nano car has four wheels, and surely the most amazing thing is how the wheels manage to move in synchrony.

The world’s smallest nano car was recently driven a distance of 6nm along a copper track. When I saw this, I thought it might be interesting to go under the hood and try to explain what makes its engine tick and its fuel work.

The epoxidation of an alkene to give an oxirane is taught in introductory organic chemistry. Formulating an analogous mechanism for such reaction of an alkyne sounds straightforward, but one gradually realises that it requires raiding knowledge from several other areas of (perhaps slightly more advanced) chemistry to achieve a joined up approach to the problem.

Following on from Armstrong’s almost electronic theory of chemistry in 1887-1890, and Beckmann’s radical idea around the same time that molecules undergoing transformations might do so via a reaction mechanism involving unseen intermediates (in his case, a transient enol of a ketone) I here describe how these concepts underwent further evolution in the early 1920s.

Fascination with nano-objects, molecules which resemble every day devices, is increasing. Thus the world’s smallest car has just been built. The mechanics of such a device can often be understood in terms of chemical concepts taught to most students. So I thought I would have a go at this one!