My university tutorial yesterday covered selective reductions of functional groups in organic chemistry. My thoughts on that topic have now morphed into something rather different. Scientific research has a habit of having this sort of thing happen.

My university tutorial yesterday covered selective reductions of functional groups in organic chemistry. My thoughts on that topic have now morphed into something rather different. Scientific research has a habit of having this sort of thing happen.

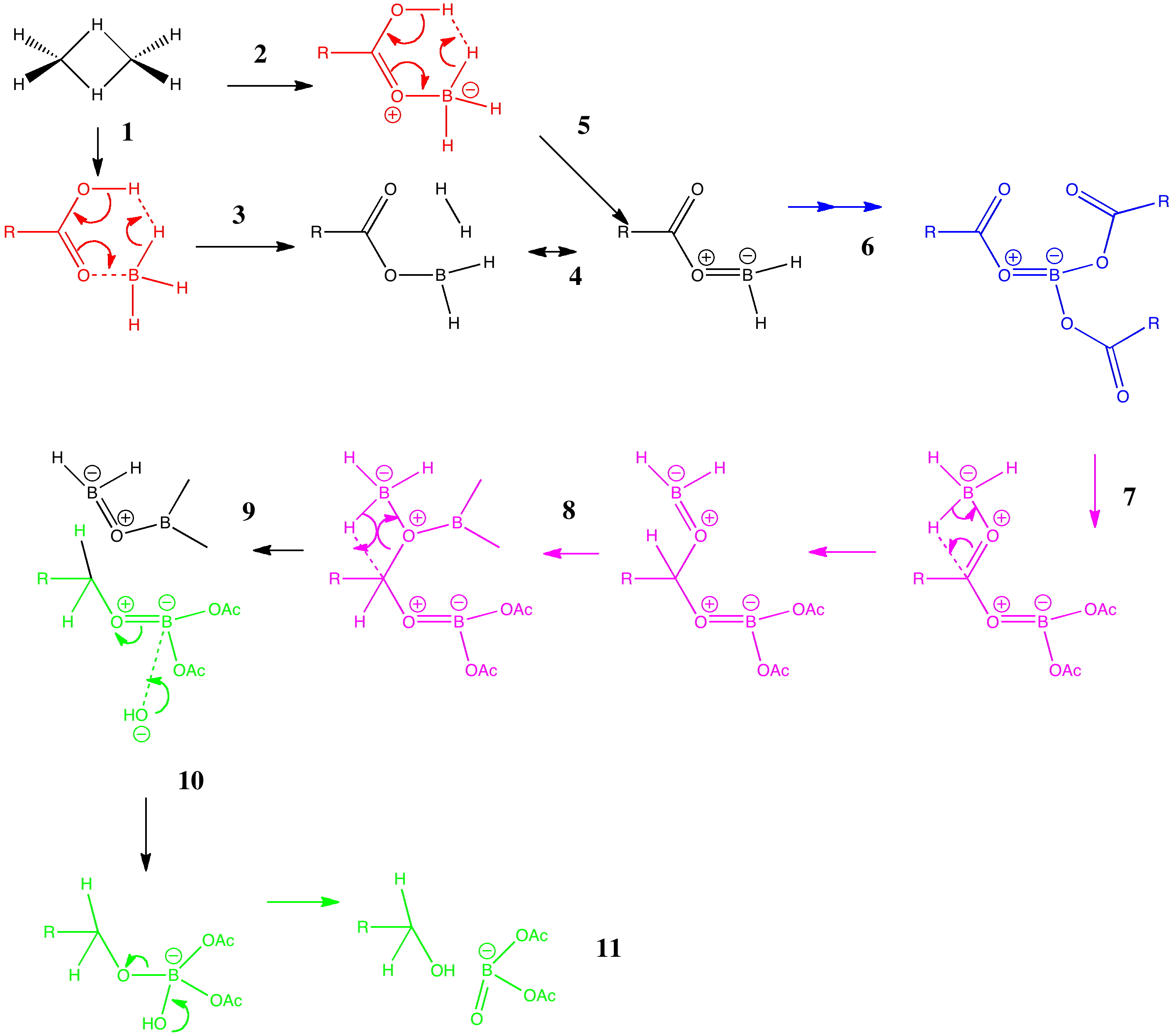

Arrow pushing (why never pulling?) is a technique learnt by all students of organic chemistry (inorganic chemistry seems exempt!). The rules are easily learnt (supposedly) and it can be used across a broad spectrum of mechanism.

For those of us who were around in 1985, an important chemical IT innovation occurred.

Our understanding of science mostly advances in small incremental and nuanced steps (which can nevertheless be controversial) but sometimes the steps can be much larger jumps into the unknown, and hence potentially more controversial as well.

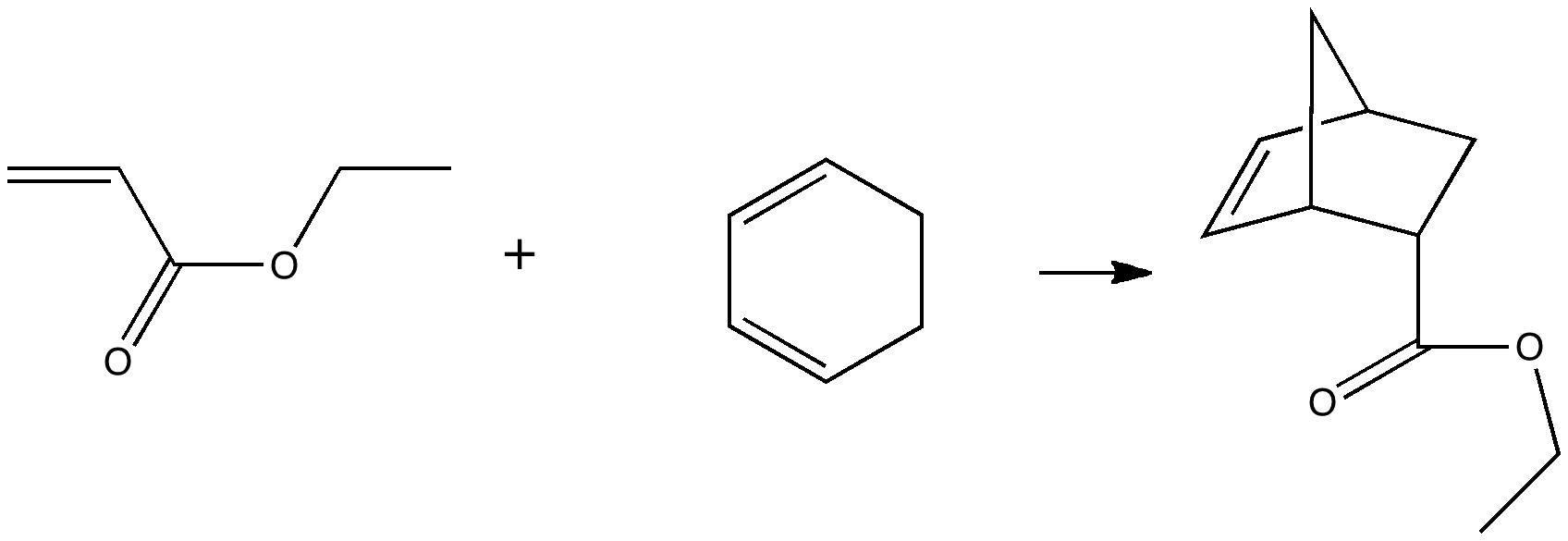

On 8th August this year, I posted on a fascinating article that had just appeared in Science in which the crystal structure was reported of two small molecules, 1,3-dimethyl cyclobutadiene and carbon dioxide, entrapped together inside a calixarene cavity.

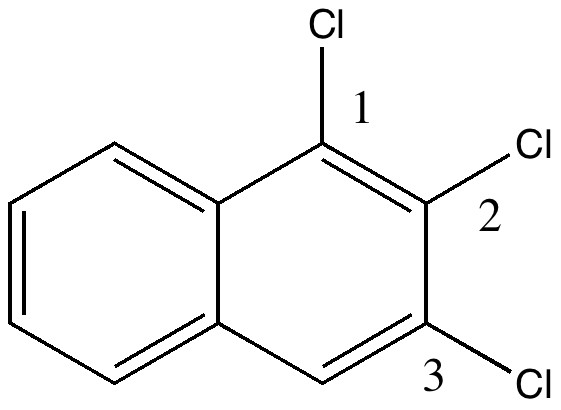

In 1890, chemists had to work hard to find out what the structures of their molecules were, given they had no access to the plethora of modern techniques we are used to in 2010. For example, how could they be sure what the structure of naphthalene was?

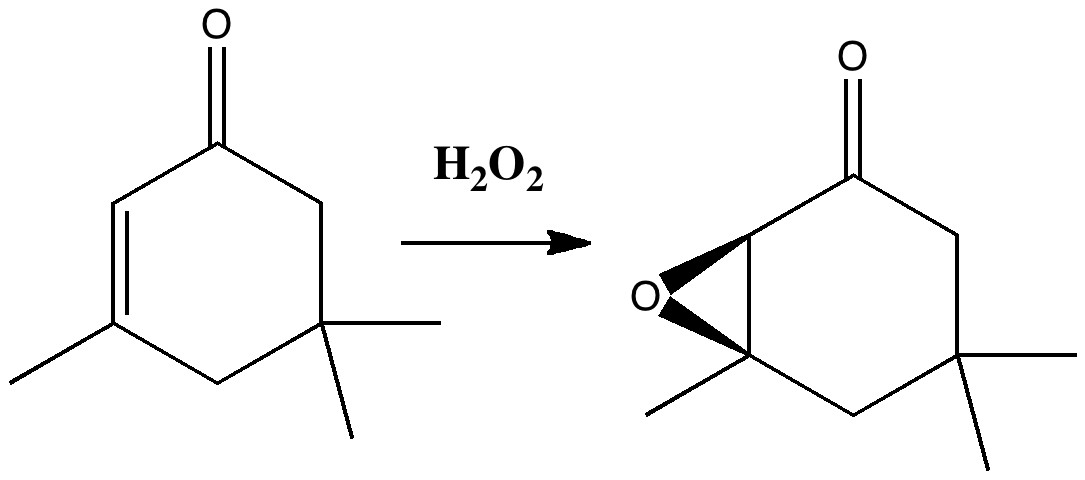

Reactions in cavities can adopt quite different characteristics from those in solvents.

Curly arrows are something most students of chemistry meet fairly early on. They rapidly become hard-wired into the chemists brain. They are also uncontroversial! Or are they? Consider the following very simple scheme.

The rather presumptious title assumes the laws and fundamental constants of physics are the same everywhere (they may not be). With this constraint (and without yet defining what is meant by strongest), consider the three molecules:

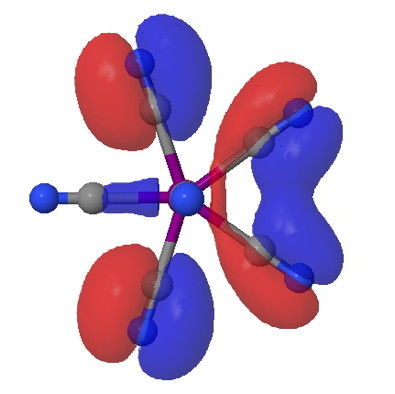

One approach to reporting science which is perhaps better suited to the medium of a blog than a conventional journal article is the opportunity to follow ideas in unexpected, even unconventional directions. Thus my third attempt, like a dog worrying a bone, to explore hypervalency.

Chemistry as the inspiration for art! The inspiration was the previous post. As for whether its art, you decide for yourself. Click on each thumbnail for a molecular sculpture (the medium being electrons!).