Previously, I wrote about various potential future roles for journals. Several of the scenarios I discussed involved journals taking a much bigger role as editors and custodians of science, using their power to shape the way that science is conducted and exerting control over the scientific process.

Corin Wagen

Who was Richard Hamming, and why should you read his book? If you’ve taken computer science courses or messed around enough with scipy , you might recognize his name in a few different places—Hamming error-correction codes, the Hamming window function, the Hamming distance, the Hamming bound, etc. I had heard of some of these concepts, but didn’t know anything concrete about him before I started reading this book.

A few days ago, I wrote about kinetic isotope effects (KIEs), probably my favorite way to study the mechanism of organic reactions. To summarize at a high level: if the bonding around a given atom changes over the course of a reaction, then different isotopes of that atom will react at different rates.

I’m writing my dissertation right now, and as a result I’m going back through a lot of old slides and references to fill in details that I left out for publication. One interesting question that I’m revisiting is the following: when protonating benzaldehyde, what is the H/D equilibrium isotope effect at the aldehyde proton? This question was relevant for the H/D KIE experiments we conducted in our study of the asymmetric Prins cyclization.

I frequently wonder what the error bars on my life choices are. What are the chances I ended up a chemist? A scientist of any type? Having two children in graduate school? If I had the ability, I would want to restart the World Simulator from the time I started high school, run a bunch of replicates, and see what happened to me in different simulations.

One of the most distinctive parts of science, relative to other fields, is the practice of communicating findings through peer-reviewed journal publications. Why do scientists communicate in this way? As I see it, scientific journals provide three important services to the community: Journals help scientists communicate; they disseminate scientific results to a broad audience, both within one’s community and to a broader scientific audience.

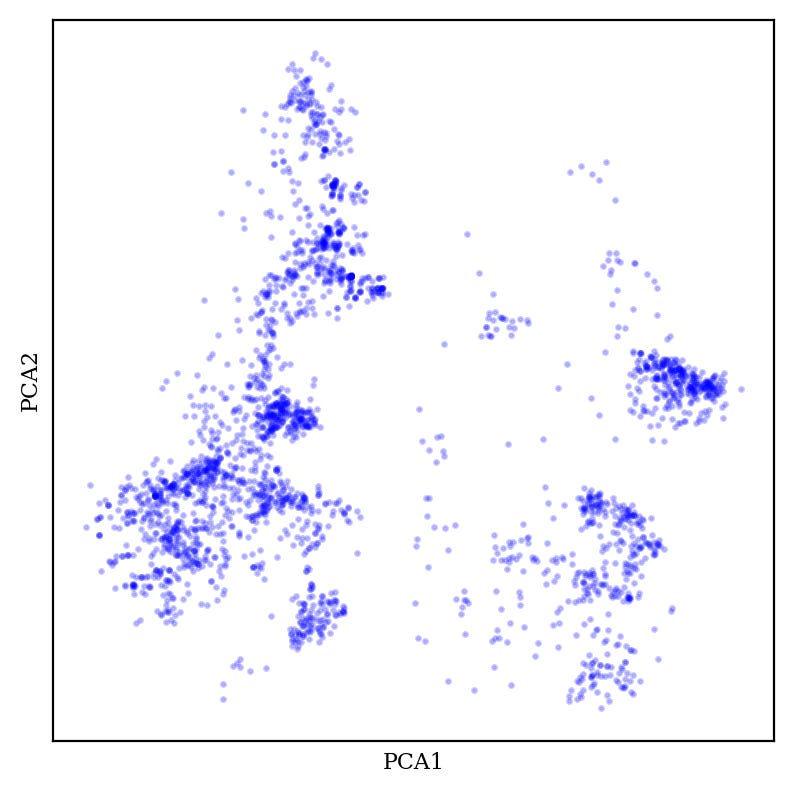

In many applications, including cheminformatics, it’s common to have datasets that have too many dimensions to analyze conveniently. For instance, chemical fingerprints are typically 2048-length binary vectors, meaning that “chemical space” as encoded by fingerprints is 2048-dimensional.

This Easter week, I’ve been thinking about why new ventures are so important. Whether in private industry, where startups are the most consistent source of innovative ideas, or in academia, where new assistant professors are hired each year, newcomers are often the most consistent source of innovation. Why is this?

While scientific companies frequently publish their research in academic journals, it seems broadly true that publication is not incentivized for companies the same way it is for academic groups. Professors need publications to get tenure, graduate students need publications to graduate, postdocs need publications to get jobs, and research groups need publications to win grants.

If you are a scientist, odds are you should be reading the literature more. This might not be true in every case—one can certainly imagine someone who reads the literature too much and never does any actual work—but as a heuristic, my experience has been that most people would benefit from reading more than they do, and often much more.

It’s a truth well-established that interdisciplinary research is good, and we all should be doing more of it (e.g. this NSF page). I’ve always found this to be a bit uninspiring, though. “Interdisciplinary research” brings to mind a fashion collaboration, where the project is going to end up being some strange chimera, with goals and methods taken at random from two unrelated fields.