We examine what generated crisis discussions, how they tended to unfold, and how they were resolved. And we derive some lessons from history for the current replication crisis.

We examine what generated crisis discussions, how they tended to unfold, and how they were resolved. And we derive some lessons from history for the current replication crisis.

This post is based on a presentation I gave in June 2025 as part of a Metascience 2025 Preconference Virtual Symposium convened by Sven Ulpts and Sheena Bartscherer and including Thomas Hostler, Lai Ma, Lisa Malich, and Carlos Santana.

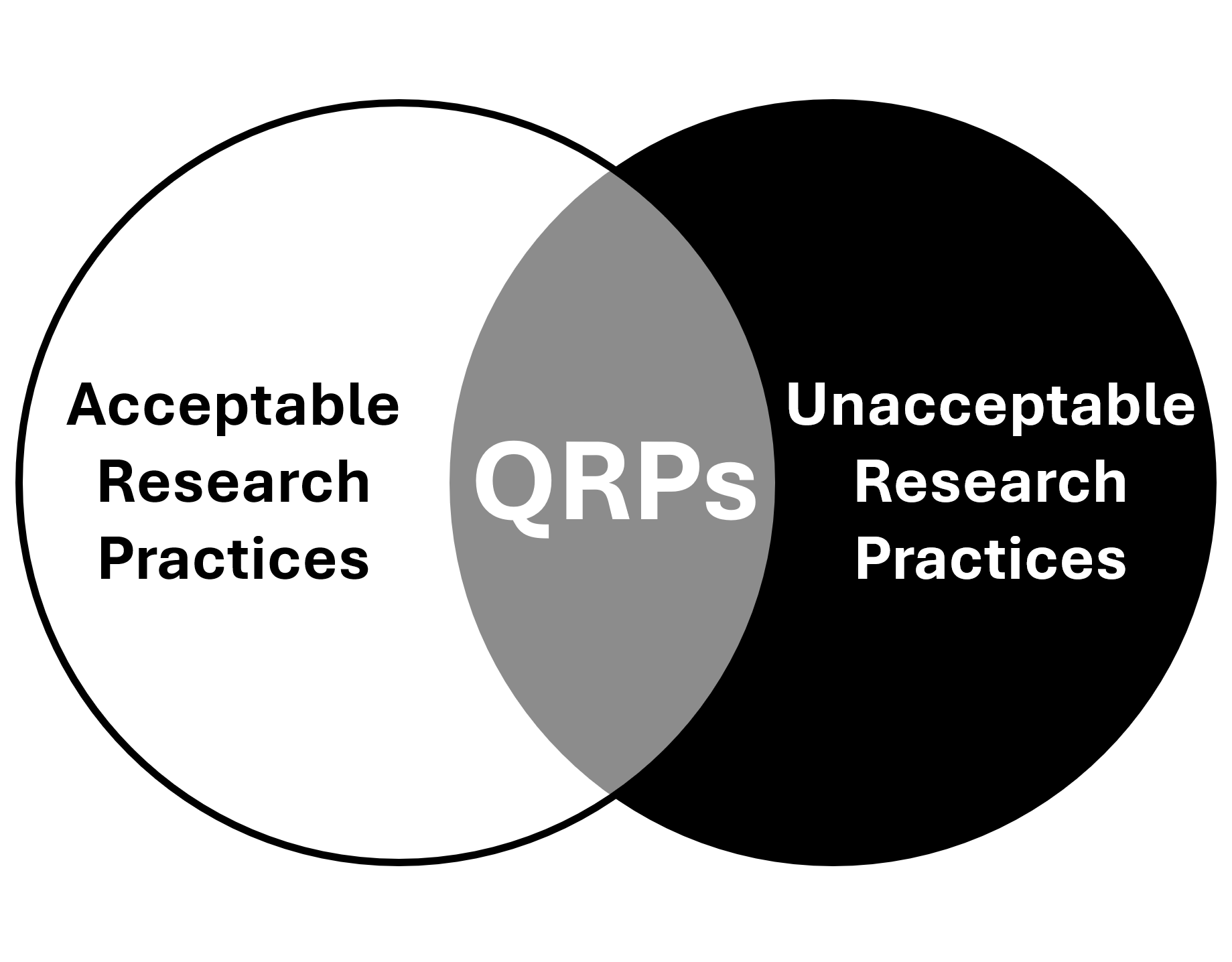

Abstract Research on questionable research practices (QRPs) includes a growing body of work that questions whether they are as problematic as commonly assumed. This article provides a brief and selective review that considers some of this work. In particular, the review highlights work that questions the prevalence and impact of QRPs, including p -hacking, HARKing, and publication bias.

Background Sparked by highly publicised cases of scientific misconduct as well as the identification of issues surrounding questionable research practices and irreproducibility of research findings, a scandalization process ensued (Penders, 2024). This scandalization initially started around narratives of a crisis concerning the research (processes) in some psychological and biomedical (sub)disciplines.

Preregistration Distinguishes Between Exploratory and Confirmatory Research? Previous justifications for preregistration have focused on the distinction between “exploratory” and “confirmatory” research. However, as I discuss in this recent presentation, this distinction faces unresolved questions. For example, the distinction does not appear to have a formal definition in either statistical theory or the philosophy of science.

An often overlooked source of the “replication crisis” is the tendency to treat the replication study as a definitive verdict while ignoring the statistical uncertainty inherent in both the original and replication studies. This simplistic view fosters misleading dichotomies and erodes public trust in science.

A conference called “The promises and pitfalls of preregistration” was hosted by the Royal Society in London from 4th-5th March 2024. Here, I discuss the presentations by Chris Donkin and Stephan Lewandowsky, both of which consider some of the potential “pitfalls” of preregistration.

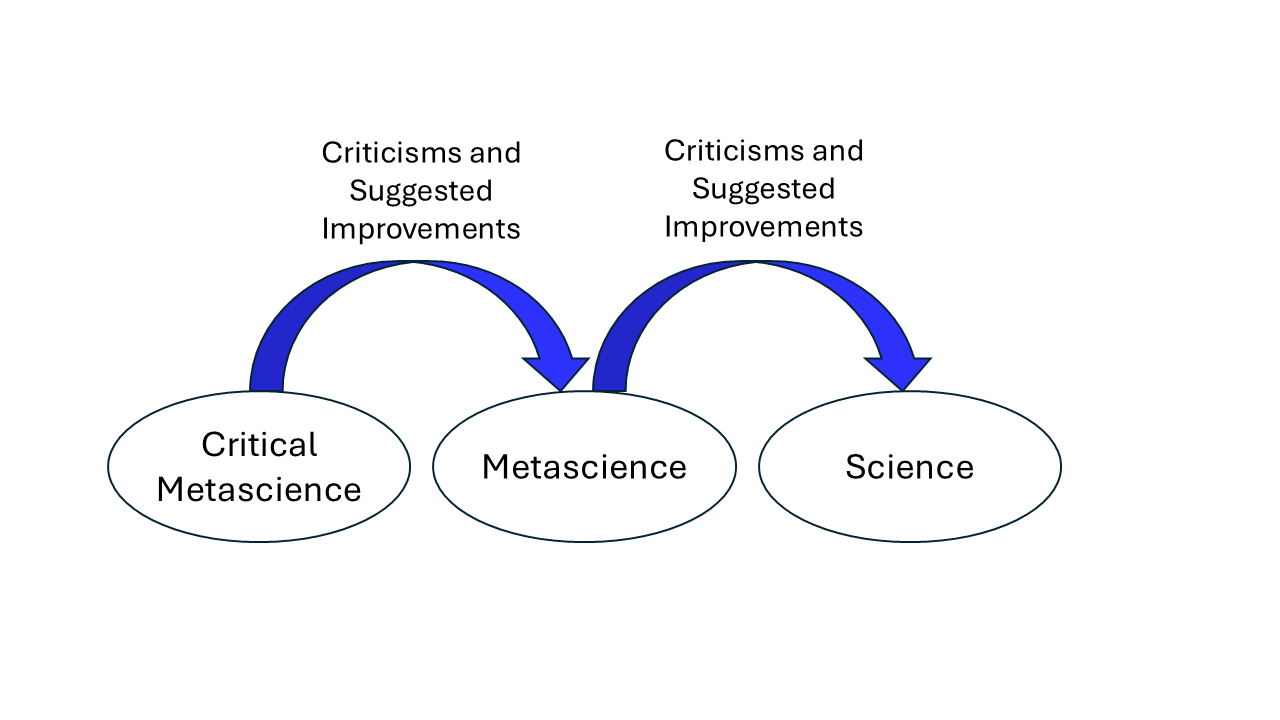

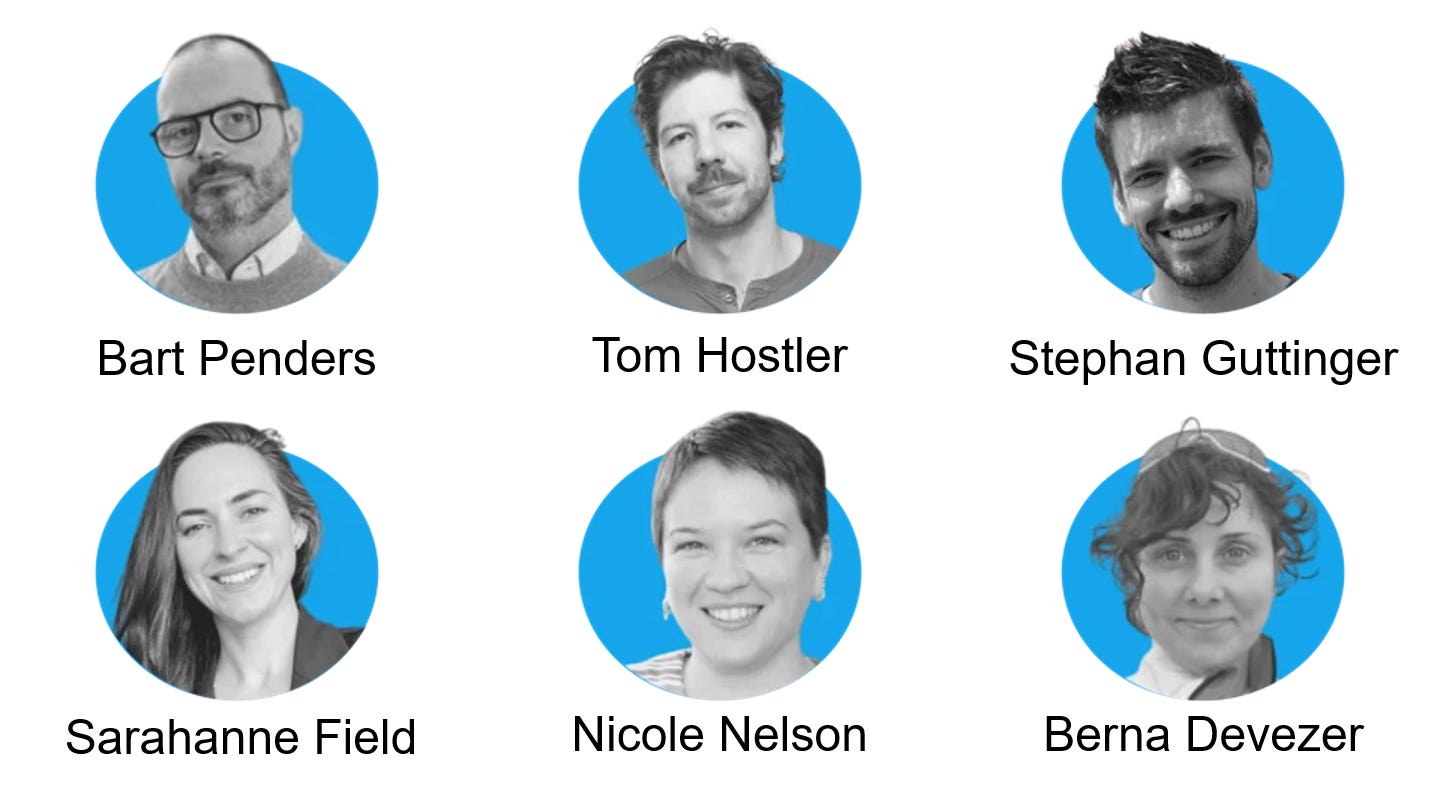

The Centre for Open Science’s symposium on “Critical Perspectives on the Metascience Reform Movement” took place on 7 th March 2024. It was organised by Sven Ulpts, and it includes presentations by Bart Penders, Tom Hostler, Stephan Guttinger, Sarahanne Field, Nicole Nelson, and Berna Devezer.

During multiple testing, researchers often adjust their alpha level to control the familywise error rate for a statistical inference about a joint union alternative hypothesis (e.g., “ H1 or H2 ”). However, in some cases, they do not make this inference.

The inflation of Type I error rates is thought to be one of the causes of the replication crisis. Questionable research practices such as p -hacking are thought to inflate Type I error rates above their nominal level, leading to unexpectedly high levels of false positives in the literature and, consequently, unexpectedly low replication rates. In this article, I offer an alternative view.

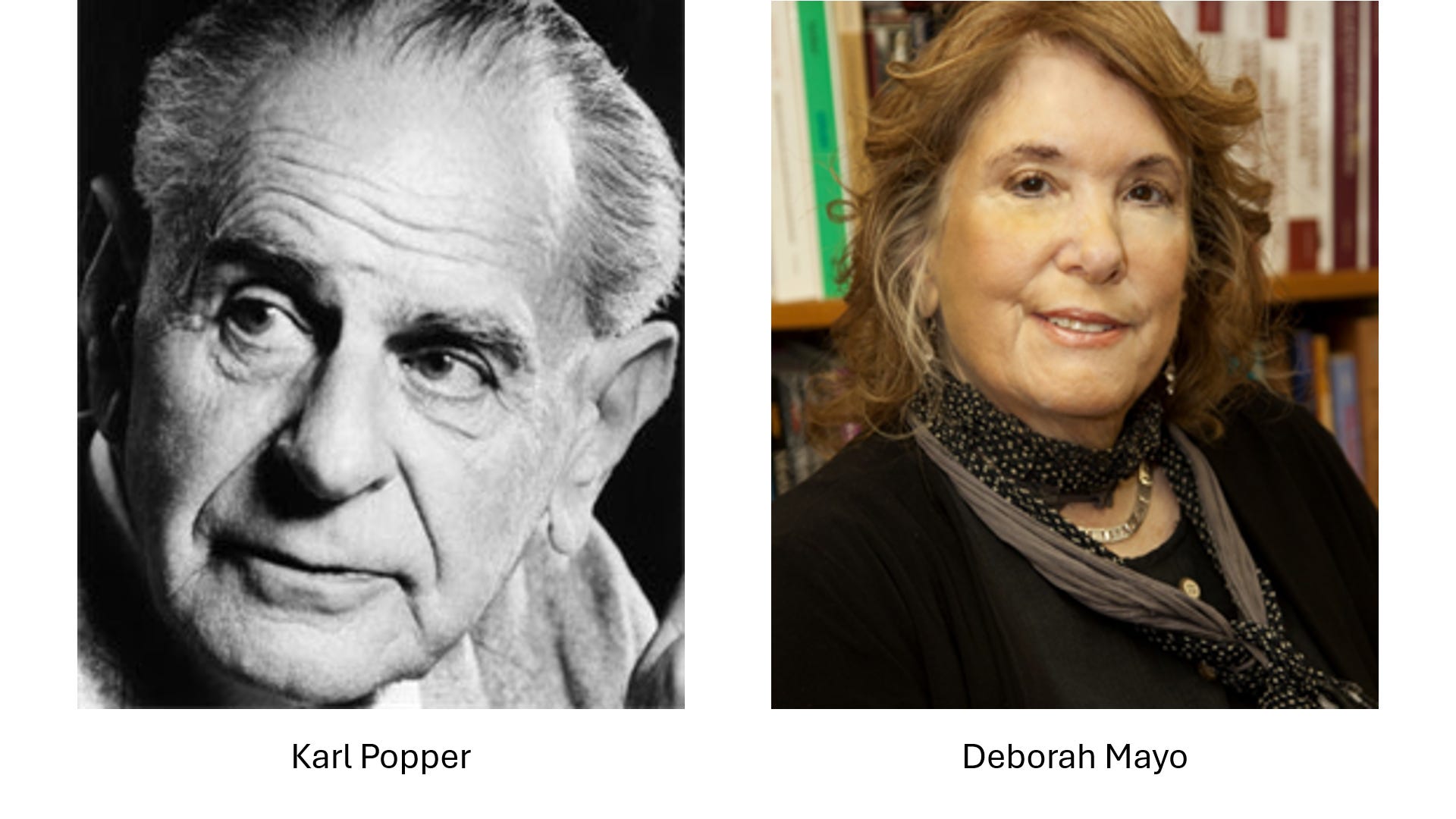

In an article published last week in Synthese, philosopher of science Pekka Syrjänen asked “does a theory become better confirmed if it fits data that was not used in its construction versus if it was specifically designed to fit the data?” The first approach is called prediction, and the second approach is called accommodation . The debate over the epistemic advantages of prediction and accommodation has been bubbling away for