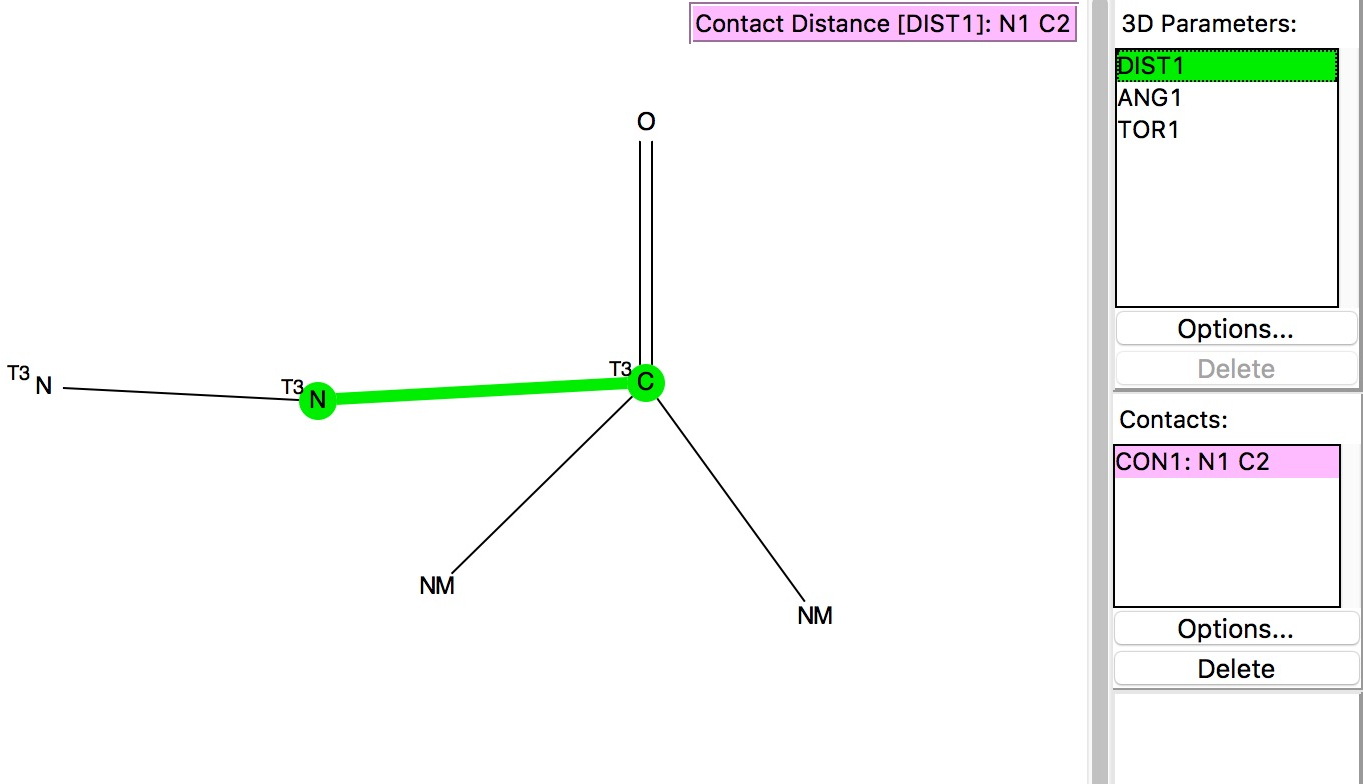

I have previously commented on the Bürgi–Dunitz angle, this being the preferred approach trajectory of a nucleophile towards the electrophilic carbon of a carbonyl group. Some special types of nucleophile such as hydrazines (R 2 N-NR 2 ) are supposed to have enhanced reactivity[cite]10.1016/S0040-4020(01)93101-1[/cite] due to what might be described as buttressing of adjacent lone pairs.