One frequently has to confront the question: will a hydrogen bond form between a suitable donor (lone pair or π) and an acceptor? One of the factors to be taken into consideration for hydrogen bonds which are part of a cycle is the ring size.

I return to this reaction one more time. Trying to explain why it is enantioselective for the epoxide product poses peculiar difficulties. Most of the substituents can adopt one of several conformations, and some exploration of this conformational space is needed.

tpap [1], as it is affectionately known, is a ruthenium-based oxidant of primary alcohols to aldehydes discovered by Griffith and Ley.

I have written earlier about dihydrocostunolide, and how in 1963 Corey missed spotting the electronic origins of a key step in its synthesis.. A nice juxtaposition to this failed opportunity relates to Woodward’s project at around the same time to synthesize vitamin B12.

The Sharpless epoxidation of an allylic alcohol had a big impact on synthetic chemistry when it was introduced in the 1980s, and led the way for the discovery (design?) of many new asymmetric catalytic systems.

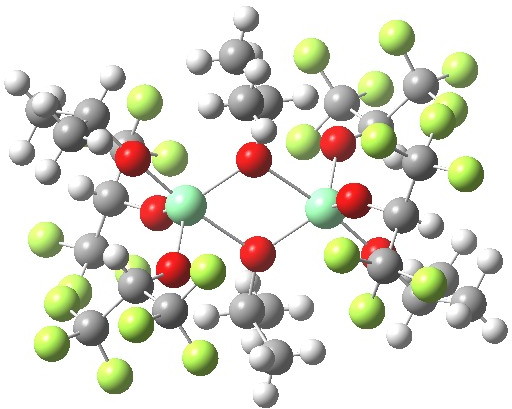

Part one on this topic showed how a quantum mechanical model employing just one titanium centre was not successful in predicting the stereochemical outcome of the Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation.

Sharpless epoxidation converts a prochiral allylic alcohol into the corresponding chiral epoxide with > 90% enantiomeric excess,. Here is the first step in trying to explain how this magic is achieved.

I noted briefly in discussing why Birch reduction of benzene gives 1,4-cyclohexadiene (diagram below) that the geometry of the end-stage pentadienyl anion was distorted in the presence of the sodium cation to favour this product. This distortion actually has some pedagogic value, and so I elaborate this here.

Birch reduction of benzene itself results in 1,4-cyclohexadiene rather than the more stable (conjugated) 1,3-cyclohexadiene. Why is this?

I promised that the follow-up to on the topic of Birch reduction would focus on the proton transfer reaction between the radical anion of anisole and a proton source, as part of analysing whether the mechanistic pathway proceeds O or M.

The Birch reduction is a classic method for partially reducing e.g. aryl ethers using electrons (from sodium dissolved in ammonia) as the reductant rather than e.g. dihydrogen.